AI was not the first image crisis: the X-ray panic of the 1890s

How X-rays brought medicine, magic and moral alarm into the 20th century

On New Year’s Day 2026 there were media reports around the world describing scenes taking place on Twitter/X, where the site’s integrated AI chat bot Grok was apparently ‘undressing’ user photos at the prompt of other users - including photos of children. At the time of writing, the political fallout has escalated to a fever pitch, and X may end up being blocked in the United Kingdom and other countries. This image crisis has been described as part of the wider novel threat of generative AI, centred on its ability to manipulate and alter images of real people to create sexualised, degrading and illegal content.

While this threat is real, especially in regard to child image exploitation, this type of image crisis is not new. In 1896 the late Victorian world was rocked by the shocking power of X-rays, an almost other-worldly technology with the frightening ability to ‘see through’ flesh, and yield a deathly visual imprint of bone and metal. Their medical and entertainment value was immediately recognised, but a cultural and moral fear took hold that X-rays heralded the complete end of bodily privacy. It wasn’t until some time later that the harmful effects were recognised, and X-rays became a highly regulated but crucial piece of our medical and security technology. There is no direct comparison obviously between AI and X-rays. but there are important similarities with how both re-render the world anew through the alteration of surface and depth, appearance and reality.

The Shock of Discovery (1895-1896)

By the time Wilhelm Röntgen accidentally produced the first X-ray images in his laboratory, the question of artificial images and their manipulations had been ongoing for over three decades. Photography and the daguerreotype exposure process had made it possible for fake images to circulate, ‘proving’ the existence of spirits and ghosts. Huge numbers of young American men had died during the 1860’s, and photographers like William H. Mumler siezed the opportunity to sell images of grieving loved ones with an ethereal person present in the frame, exemplified by his photo of Mary Todd Lincoln sitting with her dead husband standing behind her.

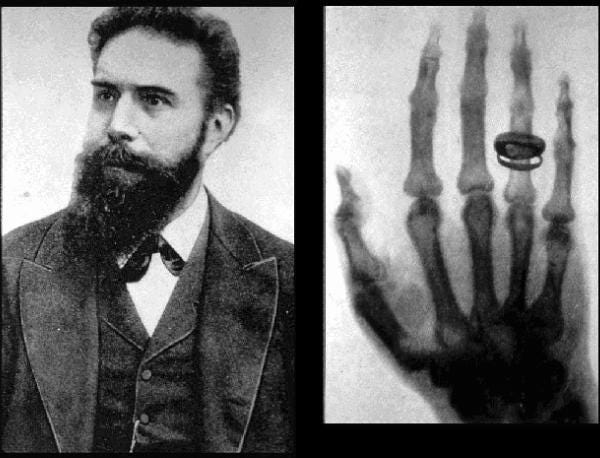

Röntgen, a German physicist, had been tinkering with running electrical wiring through vacuum tubes, and during one experiment had noticed a fluorescent afterglow.

it looked like faint green clouds … Highly excited, Röntgen lit a match and to his great surprise discovered that the source of the mysterious light was the little barium platinocyanide screen lying on the bench. He repeated the experiment again and again

-Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays (1934) Otto Glasser

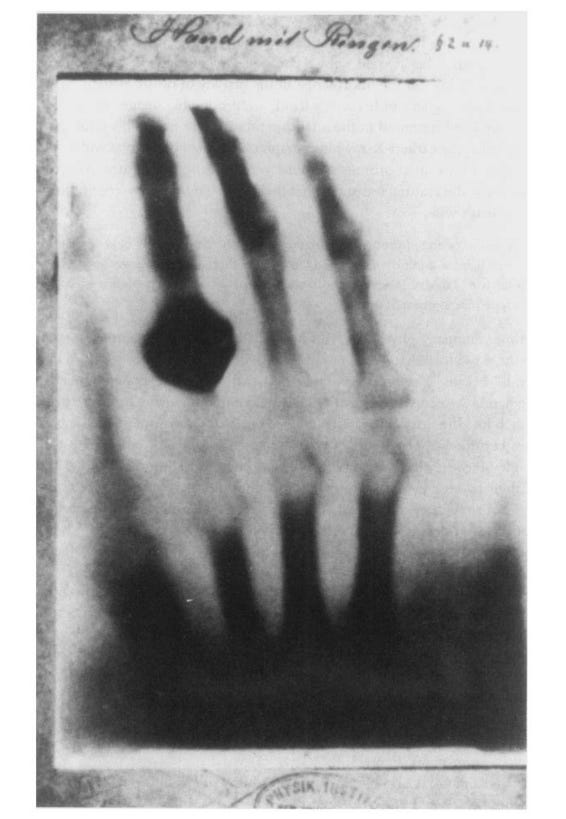

One of the first images produced using these new ‘X-rays’ was of his wife’s hand, with her wedding ring. This picture became a cultural sensation, and later many women rushed to have an X-ray of their hands with their own rings. Röntgen was unnerved and panicked by his discovery - a form of light that could peer inside the body and project the bones outwards - noone had even speculated about such a discovery. He worked feverishly and secretly in his laboratory, a quasi-Faust who had stumbled upon an occultic power. In late December, just a few weeks later, he published On a new kind of ray: A preliminary communication in a local medical journal, but this invention was not going to stay confined to the world of scientists. Within days the news hit the press, and the public were smitten. The response was, in the words of one scholar:

the most immediate and widespread reaction to any scientific discovery before the explosion of the first atomic bomb in 1945

-X Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists (1988) L.D. Henderson

The British Quarterly Review similarly wrote of X-rays in 1896, that no previous breakthrough in physics had ever

so completely and irresistibly taken the world by storm

-Anon (1896) page 496

The speed of science then compared to today is startling to consider. In 1896 alone Röntgen was awarded medals and honours by the Royal Society and the Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze; twenty lectures on X-rays had been delivered to the French Academy of Sciences by March; over 60 articles appeared in American and British periodicals by year’s end. Overall estimations suggest that between 50-60 books and pamphlets, and more than 1,000 papers were published in 1896, all concerned with the new Röntgen-rays or X-rays. In one of Röntgen’s French audiences was Henri Becquerel, who listened enraptured and immediately began working with the new technology. Becquerel discovered radioactivity that year, and published no less than seven papers in 1896. The year after, Marie and Pierre Curie began their work with radium. 1895-1896 also saw the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi patent and publicly demonstrate his new wireless telegraph system. For the public, greedily consuming all this rapturous news, the world was spinning off its axis into uncharted territory - invisible, penetrating waves of all kinds were suddenly present, peering into their bodies and carrying their messages.

The scholar Chris Otter, in his fascinating 2008 book The Victorian eye: a political history of light and vision in Britain, 1800–1910, describes how illumination through electricity and gas lamps created a new kind of society, one which managed this new capacity to see clearly by creating expectations of privacy, the interior of the home as sacrosanct, as well as new kinds of taboos (voyeurism). X-rays and other forms of wireless, invisible wave which could move through opaque defences such as walls, clothes and even skin, threatened this liberal order of light and dark. But they also confirmed and excited long-held beliefs in the ‘reality of the invisible’. Topics like auras, ghosts, the ether, spiritual mediums, telepathy and elusive knowledge of alchemy and the occult were bolstered by science. We should not forget that the simple cleavages of today - natural/supernatural, spiritual/material - did not really exist for the late Victorian and early Edwardian world. Men of science could explore the existence of the ghostly and spirit photographers could invent new ways to develop their films.

Magic & Medicine (1896-1900)

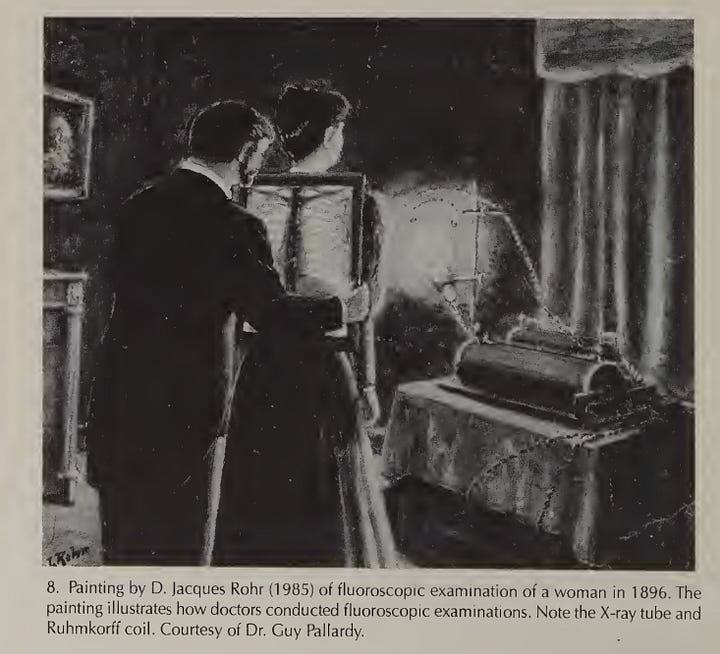

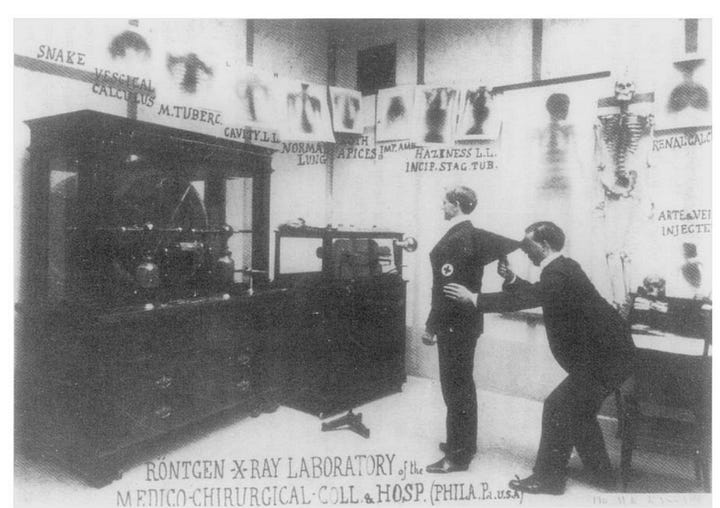

Three months after the news that a new kind of ray had been identified in Germany, one that could pass through flesh and project an image of the bones onto a plate - Thomas Edison presented the world with the fluoroscope, a real-time X-ray medical imaging machine that gave doctors an immediate advantage. See, unlike Marconi, Röntgen did not patent his X-ray technique and had no interest in commercialising the process. Therefore X-rays were an ‘open source’ and decentralised phenomenon, meaning that 1896 was a year of massive collective experimentation. Edison had not only spotted the medical benefits of photographing bone and teeth, but he upgraded the recording plate from thin card coated in barium platinocyanide or other fluorescent metal salts, to calcium tungstate, which produced a much clearer image. As hard as it is to imagine now, in the days and weeks that followed Röntgen’s paper, doctors were improvising their own glass vacuum tubes and subjecting themselves and their patients to huge doses of X-rays for up to an hour. Typically the doctor stood behind the patient, holding the recording screen and peering directly into the beam of rays to watch the faint impressions of bones appear.

In the early weeks of 1896 the international medical community was awash with anecdotal and single patient data: bullets located in bones, fractures, malformations, pathological growth and juvenile growth patterns. Teeth were also imaged. The German dentist Friedrich Otto Walkhoff X-rayed himself just two weeks after Röntgen’s publication. He devised a set-up whereby he lay on the floor with a glass plate in his mouth for nearly half an hour, directing a Crooke’s tube output straight into his face. He would go on to professionalise and institutionalise dentistry, lobbying for dentists to take a medical degree before practising. Bones and teeth were the first obvious targets of the new technology, but 1896 also saw the first imaging of human blood vessels using X-rays. In Vienna, Edward Haschek and Otto Lindenthal injected a mixture of calcium carbonate and bismuth into an amputated hand, displaying cleanly for the first time the intricate structures beneath the skin. Shortly afterwards other scientists attempted the process on cadavers, living animals and then living humans by 1923.

These practical uses of X-rays which have survived into the present were also accompanied by intense speculative and occultic ideas. One such was ‘mesmerism’, an older vitalist theory which posited the existence of a vital, universal ‘fluid’ or version of aether which permeated human beings as well as the outer world. Light and sound waves were still an abstraction to most, and although aether as a medium for wave propagation had been proven false in 1887 by the Michelson–Morley experiment, there were many scientists and physicians who clung to the idea. X-rays were a new source of hope, and researchers were soon beset with letters making wild claims. Edison reported that in 1896 an ardent fan messaged him talking of:

an English scientist who was experimenting in the new X-rays. The account stated that this scientist took a picture of his own brain while thinking of a little child who was dead. When he developed the plate he found that there was a faint impression of the child of whom he was thinking when he took the picture

- Scripts, grooves, and writing machines: Representing technology in the Edison era (1999) L. Gitelman

Telepathy and mind-reading were also suggested as possible functions of X-rays. Since they were able to surface the deep interior of the body onto a flat surface, perhaps mental information could be beamed in and out of the brain, maybe thoughts could be read and textbooks installed via these rays? Far from rejecting X-rays as crude materialism, the prominent Spiritualists and occultists of the age embraced them, watching for any connection to Baron Dr Karl von Reichenbach’s ‘Odinic’ life-force, or to resurrect spirit photography, or clues to the proposed ‘subliminal’ self, astral body, cosmic life force, bodily aura, dis-aggregated ghosts or some other term.

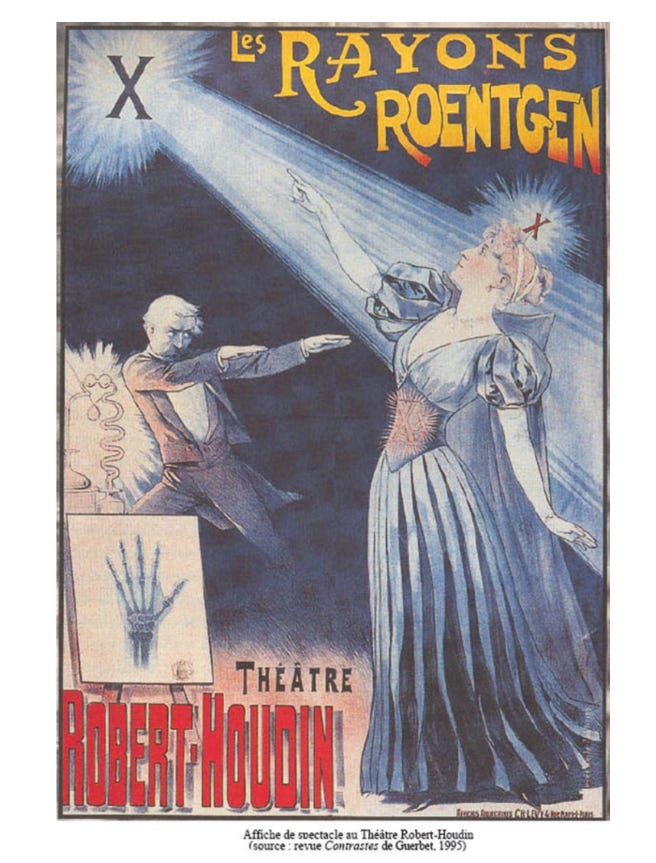

The more cynical and mercenary amongst audiences immediately spotted another opportunity - to use X-rays and their new aesthetic vocabulary on stage. Albert Hopkins’s 1897 guide to such performances, Magic: Stage Illusions, Special Effects and Trick Photography, noted in a chapter called The Neoöccultism, that magicians were actually using Crooke’s vacuum tubes to bathe an unsuspecting volunteer with X-rays and display his skeleton on a screen behind him. To the best of my knowledge nobody is sure whether X-rays were genuinely deployed as a type of showmanship, but certainly the pretence was. All manner of ingenious stage props and lighting sleight-of-hand could leave audiences gasping, as grinning skeletons appeared on the walls or in prepared coffins, most famously in the Paris Cabaret du Néant evening performance.

Magic and medicine had collided when Röntgen showed the world it was possible to pass light through the opaque body and reveal the inside on the outside. But whilst these technical uses of X-rays were being explored and discussed in the early days of 1896, the moral and spiritual panic had only just begun.

Death and Privacy in the Age of Röntgen

If you were a doctor, a scientist, an inventor, magician, patient or Theosophist, the new Röntgen rays were a practical, intellectual and career delight. For the rest of Victorian society they were somewhere between a morbid curiosity and a moral menace. London’s Pall Mall Gazette likely spoke for many when they wrote

We are sick of the Röntgen rays.. .you can see other people’s bones with the naked eye, and also see through eight inches of solid wood. On the revolting indecency of this there is no need to dwell

We are perhaps too accustomed today with invisible penetrating rays and fields to empathise with people at the dawn of the 20th century. We live amongst Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, 5G, NFC, RFID, GPS, 50 Hz electromagnetic fields from substations and charging pads, AM/FM radio, DAB, radar, LiDAR and too many others to list. Probably only airport scanners cause us enough similar discomfort, but for the public of 1896 - they had no way of knowing that X-rays would become a static, specialised and highly regulated technology.

The 1870-1880’s had seen the development of portable and near-instant cameras in public life. Gone were the days of arduous daguerreotype grim family portraits, now young men and women could use their new Kodak devices to snap pictures whenever and wherever they felt like. This very quickly developed into a battle over privacy, and camera manufacturers responded by creating some quite stunning hidden photographic mechanisms - including secret parcel cameras, proposed pocket watch and waistcoat cameras, and the quite bizarre ‘detective’ gun cameras, which were presumably aimed at people on the street. A new folk devil emerged, the ‘camera’ or ‘kodak fiend’. The Victorian Anglosphere in particular had developed complex codes of privacy, sanitation, inspection, obfuscation and signification. Slaughterhouses had been hidden away, as had corpses, private bedrooms and bathrooms had appeared, curtains for hospital patients, workhouses and factories became more observable, zoos were invented, in short the entire human architecture of city life had been remoulded for middle-class tastes and values. Who could look at who, who inspected what, what could and should be done in public versus in private or obscured.

Voyeurism and camera fiends were the equal and opposed reaction to this system. Where the power and right to view and see had become so thoroughly codified, to look where one shouldn’t was a powerful transgression. Cameras were destabilising, but also useful tools of inspection and regulation. X-rays on the other hand were a nauseatingly effective threat, with their unnerving ability to see through all the carefully arranged screens, doors, locks, walls and clothes of the average bourgeois household.

One response to this was simple panic. February 1896 saw the first London stores offering women ‘X-ray proof undergarments’, which, unless lined with lead, would have been as effective as tissue paper. Satirical cartoons and poems poked fun at the scientist’s obsession with seeing through everything

O, Rontgen, then the news is true And not a trick of idle rumour,

That bids us each beware of you And of your grim and graveyard humour.

We do not want, like Dr. Swift, To take our flesh off and to pose in

Our bones, to show each little rift And joint for you to poke your nose in.

No, keep them for your epitaph, These tombstone-souvenirs unpleasant;

Or go away and photograph Mahatmas, spooks, and Mrs. B-s-nt

-Punch, Jan 1896

The Pall Mall Gazette continued its broadside against the technology, raging that if X-rays ever came into widespread public use

it will call for legislative restriction of the severest kind. Perhaps the best thing would be for all civilized nations to combine to burn all works on the roentgen rays, to execute all the discoverers, and to corner all the tungstate in the world and whelm it in the middle of the ocean. Let the fish contemplate each other’s bones, but not us

In 1897 a 44 second-long black comedy film was made by G.A. Smith and the Warwick Trading Company called The X-Rays aka The X-Ray Fiend, wherein the actors donned black costumes with bones overlaid. The choice to expose a courting couple to X-rays so that they could ‘see’ one another ‘underneath’, says a great deal about the anxieties and amusement the public felt over this novel form of bodily intrusion.

Finding X-rays funny or a cheap form of entertainment was another immediate reaction, and arcades began a small trade in penny-slot machines. The simplicity of producing the rays meant the apparatus could be placed inside booths, boxes, cupboards and portable machines. X-ray graphics rapidly became part of early 20th centre visual culture. There were also a number of jingles and musical hall songs written in 1896-7 about X-rays and their scandalous nature, including X-Rays March Two-Step and The X Rays Will Give It Away with the latter saying

Of course, you’ve heard of the new-fangled craze,/ How things are exposed by the flash of X rays;/ The latest and greatest of fads up to date,/ That pictures your heart or your brain while you wait,/ And make it more plainer than day./ Through bone, flesh or leather those searchlights can go,/ If beauty’s skin-deep ugly girls have a show;/ That pompous policeman who paces the street,/ Will soon have to quit taking drinks on his beat,/ The X rays will give it away

-Edison’s Brain: An inside look at early recorded sound and the discovery of X-rays (2012) A. Koenigsberg

Probably the most circulated image of the day though was the skeletal, ringed hand of Bertha Röntgen. Some historians have classified it as a type of fetish object, with the fashionable women of New York lining up to have their wedding ring and hand subjected to X-rays, offering the pictures to their family and friends. The co-registration, ie the picture registering both the external ring and internal bones, makes the image so culturally powerful - a combination of the deathly with the immortal, of love and the cold grave, but also of lifelong commitment and fidelity.

Death was easily the most visceral topic to come to mind along with privacy. Our familiarity with the human body as a medical and biological sequence of layers, organs, systems and tissues makes it hard for us to empathise - but for men and women of the 1890’s, seeing one’s own hand, skull, rib cage - this was the stuff of gothic fiction and mortal dread. Bertha Röntgen herself was said to have screamed when she first saw the image; one Professor P. Czermak in Graz had agreed to have his skull X-rayed in the presence of journalists, but refused to show them the picture, reportedly saying he hadn’t slept for days after seeing his own death. A pulp horror story written in a magazine in 1896, called Röntgen’s Curse by C.H.T. Crosthwaite, followed the story of a scientist who accidentally gave himself permanent X-ray vision and went mad after seeing the ‘grinning, horrible skull’ of his wife. Röntgen was portrayed as a skeletal Grim Reaper in Life magazine, and at least one account in the Transactions of the Colorado Medical Society described seeing their finger bones appear on screen as like a hand beckoning from beyond the grave.

Sadly, whilst death was an emotional reaction to seeing the X-ray pictures, for those who were building, designing and using the machines in those early days, death was the price to pay for such knowledge.

The Martyrs and the Road to Regulation (1896-1945)

Before the year was out there were signal flares coming from all over that something was not right about the marvellous new scanning devices. They had been deployed everywhere from customs to the military to nightclubs, but the wages of innovation often include death.

Nobody knew in 1896, and wouldn’t for a while, about the danger of X-rays. One future and hugely significant use of X-rays is their ability to be fired into crystals of proteins, and the scattered diffraction patterns mathematically yield the secrets of the protein’s structure. This only works because X-ray waves are so small, peak-to-peak, they match the distance between the atoms of the crystal (approx 1.5 angstroms for crystallography). What this means for a living person is unpleasant - acute radiation burns followed by the unknown risks of cancer, as the waves pass through cells and cause damage to the complex DNA molecules.

A glassblower at Thomas Edison’s Menlo Park laboratory, named Clarence Madison Dally, insisted on quality checking each hand-made Crookes tube by bathing his hands in the active beams. It wasn’t long before his hands became swollen and burnt, but he insisted on continuing the practice. By 1904 Dally had undergone a double arm amputation, and died at the age of 39, terrifying Edison - who refused to work with or undergo X-ray screening again. Dally may have been the first ‘X-ray Martyr’, as they are sometimes known, but in the months and years post-January 1896 it had become increasingly clear that the new rays were very dangerous.

Today a chest x-ray might deliver 0.01 rads or 0.1 millisieverts of radiation. For those physicians working in 1896, who knew nothing of radioactivity, they couldn’t have known that documenting blisters, skin peeling off or hair falling out at the X-ray site likely signalled they were administering up to 1,500 rads in a single dose. The unknown calibrations, power and measurements for safe radiotherapy in those early days meant that patients and doctors, and bystanders, were absorbing higher levels of radiation than survivors of Hiroshima. Only a few other unlucky human beings have ever received higher doses than those working in 1896-1900, and the only reason deaths weren’t immediate then was the Crookes machine’s precision in producing a small, localised beam, rather than bathing the entire patient’s body.

So it was that, despite receiving radiation levels higher than Chernobyl firefighters and the unfortunate Louis Slotin of the Manhattan Project (who died following an accident with the plutonium ‘demon core’), the X-ray pioneers mostly carried on believing they were safe. Official regulation proper would not be seen until WWII, and radiology association safety guidelines were not issued until 1915 (In Britain at least). In reality it took a rising and unexplained death toll amongst doctors to force the radiology profession to take it seriously. Early opportunities were missed, in particular those from a shy and altruistic dentist named William Rollins, who published far-seeing safety recommendations in 1901-2, including: the need for lead shielding, lead painted eye protection, radioabsorbant PPE and astoundingly - ventilation for the nitrogen ozones /oxides X-ray byproducts in the room. Sadly these were ignored at the time. In 1936 the Röntgen Society of Germany unveiled the Monument to the X-ray and Radium Martyrs of All Nations in Hamburg, listing and honouring the hundreds of radiology and radiation pioneer deaths. The inscription reads:

To the Roentgenologists and radiologists of all nations,

To the doctors, physicists, chemists, technicians, laboratory assistants and nurses who sacrificed their lives in the fight against disease.

They were valiant pioneers in the effective

and safe use of X-rays and radium in medicine.

Immortal is the glory of the work of the dead

Image crises: surfaces, depths, representation, meaning

The erasure of the surface (which paradoxically renders the world and its depths and interiorities superficial), the disappearance of a discernible interiority, plunges the subject into a “universal depth.” A total and irresistible depth, everywhere.

The world is no longer only outside, but also within, inside and out …

In the X-ray image, the body and the world that surrounds it are lost. No longer inside nor out, within nor without, body and world form a heterogeneous one …

You are in the world, the world is in you. The X-ray can be seen as an image of you and the world, an image forged in the collapse of the surface that separates the two.

-Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (2005) A.M. Lippit

Manipulating the newfound properties of light, sound and different forms of energy to ‘surface’ or register hidden phenomena is one of the technological markers of the 20th century. X-rays, along with ultrasound, magnetic resonance, positron emission etc, flatten out 3-dimensional bodies into one plane, with the interior and exterior brought together. The opaque boundary of the skin and flesh failing to prevent these waves and signals from travelling through them.

Generative-AI can produce a similarly discomforting effect. Taking flattened images or videos of real human beings and apparently ‘surfacing’ superficially hidden depths. AI can do much more than this of course, and struggles with demonstrating verification and truth, becoming yet another layer of representation. X-rays are usually accepted as an accurate representation of reality, but a reality which is dehumanising - in the sense of stripping the subject of their exterior selves - requiring great expertise and experience to accurately interpret. Even so, X-ray imaging regularly feels like it violates a form of subjectivity and ownership over one’s body. A doctor or dentist informing a patient that they are currently suffering from an ailment which the patient could not sense or feel themselves, is one way that medical imaging relocates truth from the subject to the external world of physician judgement. We accept that X-rays tell us something objective, but human beings still need to perform that translation, who knows how many X-ray images are sitting in files around the world, their secrets untold.

As I said though, there is no direct one-to-one comparison between AI images and X-rays. What they both share though is the reconstruction of surfaces, depths, representation and meaning. Both prompted a social backlash, arguments about their immorality and the radical change in privacy the technology would surely usher in. X-rays ultimately became a highly regulated and specialised event, even if they were being used to measure customer’s feet sizes in shoe shops as late as the 1950’s. They also began as a very decentralised affair, their creator refusing to patent the process, and the equipment needed to generate an X-ray was easy to purchase. Their discovery was a testament to the speed of science at the turn of the century, and their subsequent uses and exploration a testament to the curiosity and ingenuity of those pioneers. Without X-rays its hard to imagine where we would be today - even a cursory glance at the list of their impact includes:

The discovery and elucidation of quantum mechanics, inc the electron

X-ray crystallography revealed the internal structure of proteins, minerals, and crucially the DNA double helix

Medical diagnostics and treatment for fractures, TB, tumour detection, dentistry, locating shrapnel

Semiconductor invention and production

Inspiration for X-ray astronomy, understanding cosmic X-ray/gamma ray production, earth’s ionosphere, creation of X-ray satellites

X-ray microscopy, revealing structures of cells, viruses, chromosomes. Also used for art, archaeology, geology and many other fields

Security and border/customs controls

It’s hard to imagine modern life without the X-ray, both confirming and disproving late Victorian fantasies of ‘hidden worlds’ and communication at a distance. I wonder if the people of 1896 would have agreed to the trade-off in privacy and bodily representation had they known about the knowledge and applications the X-ray would bring?

I’ll leave you with this poem written in 1897, and published in a popular magazine:

An Englishman’s body belongs to himself,

But surely that proverb was made

Before Dr Roentgen’s impertinent rays,

With furtive, adumbrate, and mystical ways,

Our structures began to invade.

‘T is an “habeas corpus” of uncanny source,

A forerunner of agencies evil,

A gruesome, weird, and mysterious force,

(But clothed in a garb of science of course)

A league between man and the devil.

For a steady gaze thrown on the sensitive plate.

With a one-ness of theme and conception.

And fixing our minds in a uniform strain.

Will picture the image begot by our brain.

And reveal our most inmost perception.

Who among us is safe if this can be done,

Who can bear such a scrutinization?

Scant courtesy, too, our friends would afford.

When they find that our actions are often a fraud.

And our words but mis representation

Great article, thanks