BONUS: How The Victorians Eroticised Death, From Ophelia To Salome

Sexual seances, vampires, mad doctors, the Ripper, morbid beauty, death photography, TB chic and the Ophelian aspiration

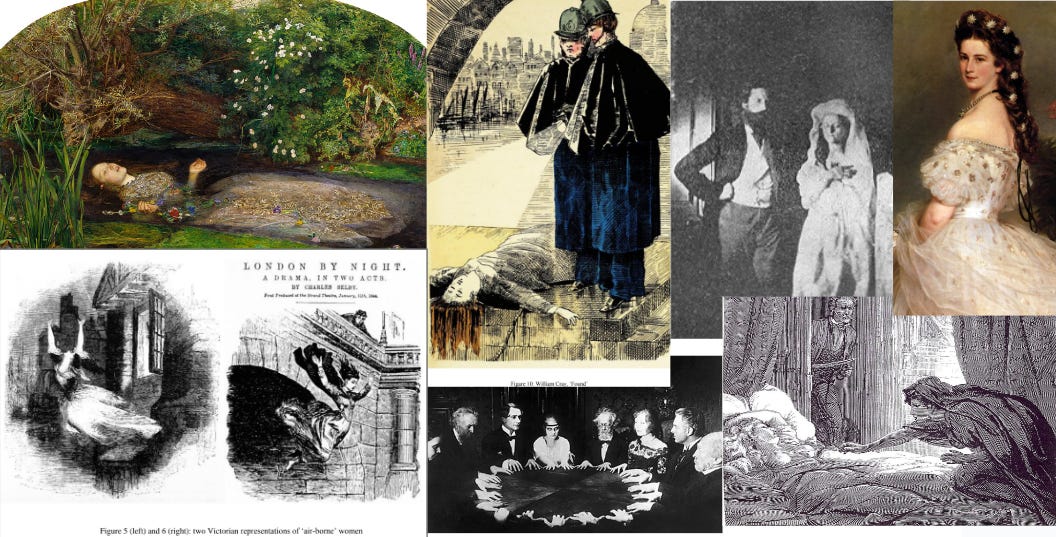

In 1569 a young Tudor woman named Jane Shaxspere slipped into a millpond near Stratford upon Avon whilst picking flowers, and drowned. We know this because in 2011 the coroner’s report of the event, almost half a millennia prior, was discovered by historians at Oxford University. They immediately linked her surname to Shakespeare himself, who would have been a boy living in the same small town when she died. One of Shakespeare’s most original and influential characters - Ophelia from Hamlet - famously drowns amid scenes of flowers and willow, and the parallels with this real and unfortunate maiden were too great to ignore, could she have been the real Ophelia? If so then her afterlife was greater than any could have imagined. As art curator Carol Keifer once wrote, “Ophelia has attained the status of a cult figure”, referenced by everyone from Dostoevsky to Taylor Swift, and yet almost no society became more enamoured by her than the Victorians. Their infatuation with the image of Ophelia, young and beautiful, drowned yet unblemished, eyes and mouth half-open, clothed yet wet, invented a powerful visual grammar of eroticised female suicide. But why would any sane culture conjure up such an apparition?

Victorian morbid eroticism went far beyond Ophelia though, to be thorough this article will cover:

Why the Victorians sexualised death

The drowned maiden, suicide and female passivity

Erotic seances, mediums and electricity

Vampires and necrophilia

The corpse in art - ballet, photography, pornography, skeleton-erotica and more

Intimacy in death, keepsakes, friendships, mourning

Medicine - body snatching, anatomical venuses, female bodies

Jack the Ripper and the invention of sex crimes

Introduction: Why the Victorians Sexualised Death

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that the Victorians were a society of highly repressed individuals, whose careful and prudish sexuality was only clumsily released in pornographic photos and the interior of sweating brothel walls. This popular truism is, however, only half-correct at best, the Victorians were indeed highly restrained when it came to all matters bedroom related, but the return of their collective repression should not be thought of as crude relief. The displacement of eros from any public expression of intimate desire could never have lingered in the background, a total misreading of how the charge of transgression operates by us moderns, no - the Victorian psyche instead shifted from the arousal of the warm living, to the morbid sublime of the cold dead. Although alien in our age of repetitive, looped and symbolically hollow digital desiring, the Victorians were drawn towards photographs of the recently deceased; the autopsy room; the anatomical perfection of idealised virginity; smooth, taut surfaces of stone and preserved flesh; nocturnal ravages by moonlit teeth on a bare neck; goosebumps after reading of yet another female murder or drowning; brushing fingertips over locks of hair cut from loved ones now entombed underground. Bataille was clear on this point - eroticism and death are always linked, the former seeking the same loss of self as the latter.

Any account of this Victorian morbid eroticism must begin with the fact that their culture was saturated with death. Rapid urbanisation, epidemic disease, industrial accidents and a depressingly high child mortality rate ensured that death was not a private anomaly but a constant public presence. Mourning practices became formalised and highly prolonged. Cemeteries became civic monuments, post-mortem photography, memorial jewellery, deathbed narratives and elaborate funerary rituals circulated widely, the morgue itself became a site of public visitation in a way that seems alien to us. All of this ‘death-theatre’ was a form of cultural management, a struggle to aestheticise, ritualise and ultimately stabilise a new overwhelming material reality.

The Drowned Maiden: A Defining Erotic Fantasy

Death is the most profound threshold and transformation in the human experience. What is left behind after a being ceases to exist is not a simple problem, anthropology is in large measure a study of Man’s anxieties around the corpse. It’s fitting that we begin with a singular strange attractor within Victorian erotic dynamics - the beautiful corpse, the beautiful corpse of a drowned virginal maiden.

The erotic vitality of young male deaths in Homer, a beautiful death with an ecstatic moment of heightened glory, was replaced during the coming of Christianity - the peak of male action swapped out for the stillness of quiet female passivity. Pagan mythology too had its sleeping beauties - Chione, Ariadne, Danaë, Psyche - and European folklore had Snow White archetypes, cementing the public equation of sleep/death/bewitched = erotic and sexual vulnerability. Tuberculosis had long ravaged Europe, but the 19th century in particular saw mind-boggling levels of infection, with roughly 25% of all deaths across the continent and the USA attributed to the mycobacterium. TB sufferers became thin, anaemic, withdrawn and frail, a condition which was romanticised and aestheticised through poets and artists. ‘TB chic’ inspired women to mimic the look through whitening and dieting, and the sought-after spes phthisica burst of euphoric creativity as the patient neared death led Keats, Lord Byron, Chekhov, Verdi and others to glorify a young, tragic death.

Suicide and water complete the morbid mise en scène. Today we probably imagine the act of taking one’s own life would have been a quiet, private taboo in Victorian public culture. To the contrary though, the newspapers loved nothing more than reporting on the lurid details of female suicide - an act strongly associated with unrequited love. A woman who had been tempted into an illicit affair with a roguish gentleman, and then abandoned, throwing herself off a bridge into oblivion: this was heady stuff, reinforcing women’s mental and physical dependency on men, and underlining their easy slide into passion and hysteria. The rash of male suicides after the 1774 publication of Goethe’s Die Leiden des jungen Werther, still referred to as ‘Wertherism’, came to be reversed. Male suicide lost its virtuous overtones and became a private affair, women’s was elevated to a public spectacle, and their bodies became a form of public property. Water also belonged to the female sphere, reflecting their changing, fickle natures, with unfathomable deepness of tide. The ‘wetness’ of the female body and its fluids, the depths of her watery womb and frighteningly unknowable sexuality both fascinated and repelled Victorian male sensibilities. The term ‘nymphomania’ was in general usage by the 1800’s, and water-nymphs were a popular artistic motif - women as seductive, alluring, dangerous. Suicide by water fulfilled all of these fantastical elements, through the gentle reception of the woman under the surface - enveloping, embracing, surrounding, submerging. Edgar Allan Poe stated, “the death of a beautiful woman is, unquestionably, the most poetical topic in the world”, and the drowning of a beautiful woman was all the more eroticised. Women jumping to their dooms in reality, sometimes with children in hand or belly, was redemption-through-death for the fallen woman. The baptismal action of drowning purified her sins, and artistic depictions of the recovered corpse often portrayed her in a white dress or gown.

The 1852 painting of Ophelia by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’s own Sir John Everett Millais, is probably the superlative example of the Victorian ‘beautiful corpse’. His model, Elizabeth Siddal, was noted as melancholic and sickly, and died of an overdose of laudanum in 1862. Like Ophelia herself, Siddal departed this world without the male preference for handgun or blade, but quietly and, one hopes, without any pain.

Erotic Spiritualism & Intimacy With the Beyond

It seems impossible to imagine that the English speaking world was swept by a religious mania for the best part of a century, a mania for speaking to the dead. Spiritualism began in 1840’s, specifically with the Fox family in 1848, Hydesville, New York. Not uncoincidentally the first full telegraph had been sent four years earlier between Washington D.C and Baltimore, Maryland. For Spiritualists, women were simultaneously active and receptive, literal receivers of electromagnetic messages made easier by their excess of nervous physiological energy - telegraphy had become a structural, explanatory metaphor within the Spiritualist cosmology. Both men and women could be mediums for ghosts or spirits, but mediumship was an inherently feminine role. To get a more accurate feeling of this period, readers should try to forget the images of haunted, dark and neo-medieval Victorianism, and remember that Spiritualism’s primary animating force was electricity. Robotics, seance communications with Samuel Morse and Benjamin Franklin, human batteries, houses with huge metal antennae. The chemist Carl Reichenbach conducted experiments in 1840’s using ‘cataleptic’, ‘feeble-brained’ and ‘neurasthenic’ teenage girls, isolating them in pitch-black rooms until they could see a ‘luminous appearance of a flaming, wave-like nature’ at the poles of powerful magnets - confirming his organic vitalist theory of additional field-forces which connected mind and nature.

Women possessing this nervous and electromagnetic connection to the spirit realm gave them social powers as mediums, engaging in medicalised, discursive warfare with sceptical male physicians over what constituted ‘proper female behaviour’. Female mediums might shout, scream, gibber, drink alcohol, flirt, convulse or moan during trances - proof of concept for a believer, proof of hysteria or epileptic lesions to a doctor. Women might contact dead politicians, Maori spirits, or lecture audiences on the plight of prostitutes using this ethereal telegraph, much as a businessman might use the physical telegraph to convey stock prices, political news or corporate instructions. Women’s passivity became a precarious source of strength, and it also began a process of erotic disembodiment. A medium was a vulnerable receptacle for external, penetrating spirits, and during private sessions they or the sitters might report being physically touched:

The Spiritualist writer and editor Mary Dana Shindler recalled being drawn to materialization séances, “Wishing to feel once more those singular touches of fingers which were certainly neither mine nor the medium’s … those mysterious touches thrilled through my soul.”

-Ghosts of futures past: spiritualism and the cultural politics of nineteenth-century America (2008) Molly McGarry.

Through this novel, para-scientific or occultic technology, both men and women could experience heterodox forms of physical and spiritual intimacy, affection, eroticism and even sex, which were strictly forbidden within normal life. Trusted female friends might caress the naked body of a medium to ensure a spiritual line of connection; male mediums would embody female spiritual affects; a medium might be stripped and tied to a chair, only to escape and cavort through the audience, planting kisses on the necks of certain favourites; spirit marriages could occur, divorces in reality on the word of a ghost. This form of eroticism drew its intensity from the polarity between the real and the ineffable, the field of electromagnetism, the ego-less empty body of the medium. Not a corpse, but not a fully living person either - not simple immediacy, but the startling strangeness of communication through a void.

Vampires & the Necrophile Lover

The erotic nature of Dracula (1897) and Carmilla (1872), of the vampire, is hardly difficult to identify. Nocturnal visitations from a seductive monster, consumed by a monstrous desire and appetite. However, vampyres were more than cheap pulp fiction. Surprisingly perhaps to modern ears, many were female, and some even seduced human women. Far from Victorian culture banning such entertainment, the undead feminine is just one more valence of the popular, morbid-erotic transgressive activities we’ve been examining.

Female bodies were believed to be more prone to disease, hence the targeting of prostitutes in the sweep of Contagious Diseases Acts of the 1860’s in Britain. Female vampires concentrated this taboo along with lesbianism, predatory masculine behaviour and the insatiability of unshackled feminine sexuality. Male vampires were re-imagined as dandyish, decadent, aristocratic - nothing like their bestial peasant origins in Transylvanian rurality. Both seduced, both dwelled in an inverted or barbaric reflection of normality, unable to withstand the light and compelled to feed only on human blood. Female vampires sometimes horrified readers by reversing motherhood and suckling from warm, living children. The biting, penetrative act of Dracula, exchanging fluids while infecting his victims, has also long been seen as a distorted sex act.

Vampires thus combined a mosaic of anxieties around sexual desire, giving space for this appetite only in the suspended space of the ‘living dead’, a person freed from social constraints, but whose body has not succumbed to decay. Erotic intimacy with a beloved corpse, necrophilic lovers, death and sex combined without reproduction of life, only of untrammelled appetite in the blood.

Corpse-Love in Art: From Skeleton-Seducers to Beautiful Deaths

As we’ve seen, the ideal feminine in Victorian art is a body without agency, suspended between life and death. Many art forms excelled in producing this body, ballet being a perfect example. The en pointe technique developed by Marie Taglioni, Comtesse de Voisins, produced an ethereal, weightless dancer who moved like a sylph or winged nymph, animated from beyond. But there was also evolution in photography and the visual arts (painting, sculpture) which took the ‘body-in-death’ idea both more literally and more symbolically simultaneously.

Death and the Maiden is a long running Western European artistic motif, dating back to the medieval era and beyond. Death, often portrayed in a grotesque, almost lecherous fashion, lusts after a young woman, lining up Eros and Thanatos cheek-to-cheek. In the late 1700’s and the early-to-mid Victorian period, this motif is re-imagined, and death becomes a beautiful young woman herself. This changes again during the 1880’s and especially the 1890’s with the Decadent/fin de siècle movement, and death once again becomes a skeleton, although an explicitly eroticised one.