Did the Inuit invent Rap?

Aggressive verbal duels in Homer, the pastoral world and the Arctic. Some polar ethnomusicology, throat singing, beatboxing.

In this linguistic duel, two [Inuit] men, at least one of whom possessed some form of bitterness towards the other, would take turns at singing ironical songs of their composition, in order to make fun of their opponent. The loser was the on who finally abandoned the contest when he was no longer capable of ridiculing the other.

-Grasping the Power of Language: Name and Song in Inuit Culture (Tina Pylvainen)

Þórr qvað: „Hins viltu nú geta, er við Hrungnir deildom, sá inn stórúðgi iotunn, er ór steini var hǫfuðit á; þó lét ec hann falla oc fyrir hníga. Hvat vanntu þá meðan, Hárbarðr?“ Þórr said: “This is what you’re talking about, that Hrungnir and I fought, the great-spirited giant, whose head was made of stone; and yet I brought him down and made him fall before me. What were you doing in the meantime, Hárbarðr?” (St. 15)

Hárbarðr kvað: ”Var ek með Fiolvari fimm vetr alla í ey þeiri, er Algœæn heitir; vega vér þar knáttom oc val fella, margs at freista, mans at kosta.“ Hárbarðr said: “I was with Fjölvar five winters long on that island called All-green; we fought there and wreaked slaughter, we tried out many things, had our choice of girls.” (St. 16)

-Hárbarðsljóð from the Poetic Edda

The two women, dressed in furs, grasp each other by the arms and come face to face. A stream of rhythmic punctuated sounds begin to issue forth from them, some like escaping air from a sealskin, some like harsh feline growls. They press their faces closer, their breath mingling as they almost stab one another with each exhalation, before they finally collapse into the snow, laughing hysterically. Called katajjaq in Nunavik, the Inuit practice of female competitive throat singing is an interesting counterpart to the male practice of verbal duels mentioned above. Katajjaq shares many similarities with other circumpolar throat singing and musical practices, including the intense use of environmental and animal mimicry, as well as the sharing of breath and use of another person’s mouth as a resonance chamber for notes and sounds.

Katajjaq is a friendly and light-hearted competition, but it fits into a style of verbal/oral duels which take on many forms all around the world. In the west today we only really experience agonistic linguistic conflict in one place - rap/hip-hop and their derivative subgenres. In fact the idea of two men squaring up to one another and trading rhyming insults in lieu of real violence seems anachronistic, backwards even. Even so, competitive verbal contests remain at the heart of human civilisation - in law courts, debates, parliaments and senates, in the words of opinion writers and gossip columnists, in doctorate and professorial vivas and appointment hearings, cross-examinations, academic presentations and in conference Q&As.

In many historical periods, indeed in most cultures whose state of records permits speculation in the matter, socially legitimated forms seem to have been created for the verbal expression of adversativeness. The highly distinguished and various career that the verbal contest has sustained in the history of human cultures attests to the significance and dynamicism of the adversarial relationship as one of the prime determinants of human behavior

Contests, as others have shown, are an expression of an indigenous human urge toward ritualized combat… By means of the contest, the participant is able to establish identity - and particularly sexual identity - in a public way. Thus the ritualization of contest is not at all externally added on, the imposition of a community fearful of unrestrained displays of aggression. On the contrary, it arises out of the very nature of contests themselves. For the proving of selfhood is inextricably tied to the role of the individual within his social group. The ritualization of contests provides the means by which these individual displays can become invested with public meaning

-Flyting, Sounding, Debate: Three Verbal Contest Genres (1986) Wards Parks

The initial question, ‘did the Inuit invent rap?’, is an obvious nonsense - but it provides a great framework for exploring some of these verbal contests and duels, as well as some features of circumpolar music, in particular throat singing and other unusual vocal techniques. So let us begin in that most appropriate of places - with Homer

Homeric and heroic insults

The term flyting comes from the Old English flītan, meaning ‘to quarrel’. Although it is strongly associated now with Scottish and other North Sea cultures, the term is often used academically to refer to verbal duels made in public between any two individuals, usually men, and often for the entertainment of those watching. Flyting covers all sorts of verbal contests: trash-talking, insults, boasts, rhyming attacks, barbed plays on words, structured verse and poetry, preludes to actual combat and straight up scatological comedy. For a literary example we can turn to Act Two of Henry IV, where Hal and Falstaff let fly some golden insults at one another:

PRINCE These lies are like their father that begets

them, gross as a mountain, open, palpable. Why,

thou claybrained guts, thou knotty-pated fool, thou

whoreson, obscene, greasy tallow-catch…FALSTAFF ’Sblood, you starveling, you elfskin, you

dried neat’s tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stockfish!O, for breath to utter what is like thee! You tailor’s

yard, you sheath, you bowcase, you vile standing

tuck—

PRINCE Well, breathe awhile, and then to it again, and

when thou hast tired thyself in base comparisons,

hear me speak but this.

Engaging in insulting, crude verbal spars has always been part and parcel of the heroic mindset. Public boasts and drinking contests, oaths and duties, the swearing of allegiances, the settling of scores, revenges against insults to one’s honour and the power of humour and wit to defeat a rival in the eyes of their peers - all these appear throughout heroic and warrior literature. For the Islamic world, they had naqa’id poetry, for the Norse they had senna, and for the Greeks they had neîkos.

The Homeric world itself is also full of heroic jabs, mockery and hostile trash talk.

neîkos in the Iliad and its generic equivalents share certain broad features. All involve antagonistic speeches composed of ritual abuse, vows, threats, and boasts… in an epic flyting two warriors come face to face, the challenger makes a Claim, and the challenged in turn makes a Defense and Counterclaim before the contestants proceed to physical fighting.

-Talking Trojan: Speech and Community in the Iliad (1996) Hilary Mackie

The heroic figure is of course different to the ordinary community from which he is drawn. He might have warrior kin and peers, but he is apart from the ordinary rank-and-file. Within his band, his friends, there will be competition and rivalry - but this rarely breaks down to lethal violence. On the other hand, the hero could be expected to fight a solo combat, partly to redirect mass violence and casualties towards one skillful duel, and partly to display his fearlessness and abilities. Insult verse and structured lines of threats and abuse therefore help prevent violence when between friends, but act as a on-ramp to violence when hurled out before a fight. This tension between verbal duels as a group safety valve but also as a way to cross the threshold into real violence is present wherever it is found around the world. The scholar Wards Parks offers a cohesive explanation to unite this tension in his book Verbal Dueling in Heroic Narrative (1990)

Deadly combat flourishes most in inter group settings, although here too, since contests as rule-governed interactions are built on the recognition of reciprocity, the flyting negotiative process offers loopholes by which fighting can be avoided. Even mortal enemies, if they are engaged in long-term warfare, come to recognize the need for certain reciprocal observances. Thus, the Trojans and Achaeans in book 3 of the Iliad try (though unsuccessfully) to make a single duel between Menelaus and Paris substitute for continued hostilities between the armies.

He goes on to argue that flyting can only exist in a situation of reciprocity, since predators and threats from outside the human realm cannot and do not engage in it. Grendel, the Cyclops, wild animals - duels with these beings do not observe rules of combat nor of wit, nor can they be avoided or defused with language. Ironically our capacity to insult one another has probably saved more lives than it has cost.

Ancient Greek literature approached the neîkos in different ways depending on the genre. Whilst Homeric and epic poetry use the quarrel as the prelude to a formal physical duel, iambic poetry turns the neîkos into an entire literary style. Iambic ‘blame’ poetry is a form of controlled aggression, sometimes more light-hearted and satirical, sometimes full of invective and bitterness. Some verses from Epode 10 of Horace illustrate this well, full of hatred for the poor anonymous Mevius.

The ship casts off from shore in an ill-omened hour,

Carrying the stinking Mevius.

God of the southern wind – take care to pulverize

Both its sides with horrendous waves!Let the black eastern wind turn the sea upside-down,

Some oars here, some rigging there,

And may the north wind loom as large as when it rends

Oaks trembling on the mountain tops,That time Athena turned her rage from smouldering Troy

Onto Ajax and his damned ship!

Oh what a cold damp sweating will beset your crew

While you change hue to a pale green,

Bucolic or pastoral poetry/literature in the Greek world also featured the neîkos, but in yet another form. Here in the world of the shepherds the flyting and quarrels between men high up in the hills also turned into a formal contest, but rather than with swords and shields - these men would sing mocking and sharp songs at one another in the presence of a judge (known as Amoebaean singing). In all these examples the quarrel is a public spectacle rather than a private fight, the victor decided by witnesses. Heroic taunts and boasts exist all over the world, wherever heroic martial cultures take root - but the ancient Greeks with their foundational cultural roots deep in the agon, the competition as the source of existence- elevated the verbal contest for multiple walks of life.

Pastoralists & Poetry

As we go deeper into types of formal verbal/sung duels around the world it is worth listing out some examples, many of which are still practiced today:

Norse / North Atlantic

Flyting / senna / mannjafnaðr (Viking & medieval Scandinavia/Scotland): Verse-insult and “comparison of men” contests

Classical Mediterranean

Amoebaean singing (ancient Greek/Roman): Competitive “answer-song” poetry in Theocritus’ Idylls and Virgil’s Eclogues, foundational for European “song contests.”

Caucasus / Central Asia

Aitys/Aitysh (Kazakh/Kyrgyz): Improvised sung duels between akyns with dombra/komuz

Meykhana (Azerbaijan): Improvised rhymed duels in a 6/8 time signature, has been described as a local rap tradition

Middle East

South Asia & Himalaya

Southern Europe & Mediterranean

Bertsolaritza (Basque Country): High-level improvised sung verse contests

Sardinian poesia estemporanea (Italy): Public improvised verse jousts

Portuguese desgarrada: Accordion-backed improvised duels, again described as ‘rap’

Maltese għana (spirtu pront): Improvised, witty multi-singer duels, less competitive

Cretan mantinades: Competitive improvised couplets

Turkish âşıklık ‘minstrelsy’: Traditional nomadic folk poet-singers, one of their many skills is the art of verbal/lyrical duelling, also known for other challenges like holding a pin between the lips (lebdeğmez) and reciting without the letters ‘p’ ‘b’ ‘m’ ‘f’ and ‘v’.

Latin America

Payada / paya (Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay): emerged from Guacho culture, payada guitar-accompanied poetic duels, make use of a beat sometimes

Repente poetry/song (NE Brazil): Different forms exist, use of two players with instruments singing/verbalising funny, clever songs, sometimes in duels other times duets.

Africa

Halo (Adja-Ewe of Ghana, Togo, and Benin) insult poetry and performance, mocking ritual against warriors

Udje (Urhobo of Nigeria) dance/poems between rival towns/villages, often scathing/insulting or lampooning criminals and social deviants

Yabis (Nigeria) contemporary insult poetry duels, known to use modern Afrobeats music

Taarab (Swahili/East Africa) sung poetry duels/competitions, can be insulting, predominantly female

This is by no means a complete list, but even so it is striking how often this form of solo conflict-poetry appears in nations, regions and peoples strongly connected to shepherding and pastoralism. This includes South American Gauchos, Arabian camel herders and Cretans tending their goats in the rocky hills. By contrast the African examples showed more communal tendencies, entire groups using lyrical satire to deflate the egos of strongmen and criminals. The connection between pastoral life and verbal sparring has not been discussed much in any literature I can find. Anthropologist Elizabeth Mathias wrote an article in 1976 describing her fieldwork in Sardinia, wherein she explained:

The Sardinian shepherd’s code of onore has developed out of basic needs in his society which place a high premium on individualism, independence, and the ability of the individual to defend his personal interests… Performance of La Gara Poetica in the ovile acts as a way of channeling the shepherd’s intense individualism into an expression of power.

-La Gara Poetica: Sardinian Shepherds’ Verbal Dueling and the Expression of Male Values in an Agro-Pastoral Society (1976) E.Mathias

The rough, often brutal world of cowboying, cattle rustling, racing camels and horses, protecting flocks against wild animals and defending one’s honour lends itself well to clashes of individual pride and reputation - boasts about young women bedded, fights won and even rivals killed flow easily alongside a declared love for horses, cows, animals, the quality of their meat, milk and wool or how much they sold for at market. For a shepherd almost everything is a challenge, a threat to their herd and family, including other shepherds. In this way the pastoralist and the hero are very similar.

Deeper than words - poetry, music and throat singing

The human voice is amongst the most expressive in the animal kingdom, partly because we have conscious control over our breath, and partly because we have accreting cultural mechanisms to learn sound-making skills rather than inventing them with each generation. The result is a global soundscape which has recently become sadly narrowed and homogenised. One can look up Scandinavian kulning, Croatian ojkanje singing, Alpine and Central African yodelling/yelli, the endlessly entertaining Balinese kecak performance, Xhosa click-tunes, Korean pansori, the Sami joik and modern metal screams and growls for some inspiration.

Music does seem to be a human fundamental, to my knowledge there are no known human societies which lack the ability to make and understand music. The brain is adept at and adapted to processing sounds as they are experienced by the listener - melody, pitch, rythmn, harmony and, most crucially, these sounds are experienced emotionally. It barely needs to be said that music can make us weep or move us to anger, feel love or joy or the need to move, because most of us have all felt that. In Oliver Sack’s wonderful book Musicophilia, he shows that the brain is normally so engaged and so stimulated by listening to music, it becomes a form of syndrome or a neurological symptom (known as ‘amusia’) when the brain fails to correctly process it.

Nevertheless, culture is the major determinant in what kind of music developed where. European hegemony over the development of musical composition, expression, technique, theory and melody is unrivalled - with most music around the world remaining wedded to strict traditions and conventions. However, there are sounds and skills from elsewhere to be discussed, one of which is throat singing. The name throat singing is recognisable to many today, although it does not accurately reflect the sound that is being made. Most people think of the deep Mongolian/Tuvan form, but the main principle is that of overtone singing or polyphonic singing. This refers to the sound of one human voice which can make two or more distinct notes, usually a lower ‘fundamental’ note and a higher ‘overtone’ note. Overtone singing itself has emerged and branched away from traditional throat singing (you can search Anna-Maria Hefele or Wolfgang Saus), and Tuvan throat singing also contains many complex and subtle techniques, which makes the term throat singing hard to define.

Cultures that have developed forms of throat/overtone singing - many Turkic, Siberian, the Chukchi, Inuit, Balochi, Sardinian, the Xhosa - often reference the ability of the sound to travel well through the large empty spaces or mountaneous regions. In the song Anoana by the band Heilung, one of the vocalists uses a kulning-esque herding vocal technique which cuts through the air like an alarm, similarly Altai throat singing overtones can be very high and bright sounding. Another common reference is the mimickry of nature, singers attempting to copy the sounds of the wind, different birds or animals, the noises of water, ice or storms. Thankfully these once obscure singing techniques have become incredibly popular - in bands and groups like The Harmonic Choir, Old Norse covers, Siberian Chulym’s Otyken, Mongolia’s folk-metal The HU, Buryat singer Aryun-Goa and in whatever this Khoomei ‘throat-techno’ is.

Arctic music, beatboxing and final thoughts

In a 2012 paper called ‘Animal Impersonation Songs as an Ancient Musical System in North America, Northeast Asia, and Arctic Europe’, the independent scholar Richard Keeling proposed what he called The Northern Hunting Religion - an assemblage of shared beliefs and behaviours which spread across ancient Europe, Siberia and North America. The core features of the religion were:

Annual ceremony for major game animal (salmon, whale, or bear)

Propitiation of game animals through spoken prayers and other offerings

Concept that animals are immortal and only give flesh temporarily

Concept that animals are conscious of human intentions

Ritual disposition of bones and unused parts from game

Sexual and other restrictions to avoid offending game animal

Fear of menstruation and ambivalence toward female sexuality

Specialized shamanism involving possession by animal spirits, and

Songs imitating the voices of mythic animals or other spiritual entities

The last of these, that songs and music are rooted in the imitation of animals (even mythical ones), does fit with other scholarship about Arctic/circumpolar musicology, even if the rest of the religion may not be.

Suddenly he commenced to beat the drum softly and sing in a plaintive voice: then the beating of the drum grew stronger and stronger; and his song—in which could be heard sounds imitating the howling of the wolf, the groaning of the cargoose, and the voices of other animals, his guardian spirits—appeared to come, sometimes from the corner nearest my seat, then from the opposite end, then again from the middle of the house, and then it seemed to proceed from the ceiling. He was a ventriloquist. Shamans versed in this art are believed to possess particular power.

-The Koryak (1908) Waldemar Jochelson

The development of music and song with animals is likely bi-directional, meaning that many northern pastoral musical traditions may have evolved out of the need to communicate with animals. The scholar Aleksey Nikolsky has recently argued in a 2020 paper called The pastoral origin of semiotically functional tonal organization of music, that yodeling, kulning and later hollering, are distinct forms of a broader Indo-European ‘cow-language’, whereas Finno-Ugric cultures have created their own ‘reindeer-languages’ with specific vocalisations. Lulling, milking-songs, calling-home, ‘motherese’ soothing music-speak for new calves - all fall into a distinct vocal register which animals can interpret as safety, and all exist/existed across the northern pastoral world from Scotland to Sweden to Altai.

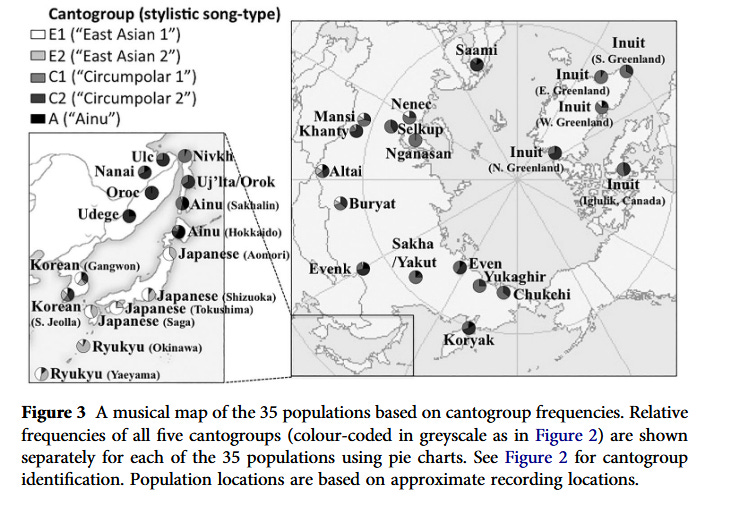

In contrast to domesticated animals, wild animals can also understand human songs, but these are not the clear high harmonics which signal protection. Arctic peoples such as the Sami are known to sing or joik specific songs to specific animals - ie the ‘bear’s song’, or the ‘elk’s song’. The concept of a ‘personal song’ also exists amongst the Inuit and the Sami, an idiosyncratic melody/rythmn which can be intensely personal and rarely if ever vocalised. More broadly however, animal imitation forms part of the well-explored circumpolar/circumboreal musical repertoire. According to ethnomusicologist William P. Malm, this region around the Arctic, encompassing the Ainu, Sami, Siberian peoples, Aleuts, Inuit and some other Native Americans, displays a roughly shared musical lexicon of: animal imitation sounds, breathing/sound games and harsh, throaty utterances, use of framed drums, an acceptance of loose sing-speak epic chants or narratives, use of timbre-rich instruments such as the jaw harp and various local zither/lute variations. Studies of how well the Ainu fit into this pattern have been fairly extensive, including a 2015 article called How ‘Circumpolar’ is Ainu Music? Musical and Genetic Perspectives on the History of the Japanese Archipelago, which attempted to fit the Ainu musical heritage with their known genetic admixtures.

One of the reasons for the focus on the Ainu over the years was the discovery that some Ainu engaged in a very similar breath game to the Inuit, known as rekuhkara. A modern recreation of this can be watched here - listen out for the obvious animal noises and distinctive breath control/beat, but also notice that the players are making noises into each other’s mouths, with the aim of the using the mouth and throat of the other player to resonate and modulate the sound. Good players are supposed to recieve the sound from the other, and modify their larynx and mouth shape, like singing backwards.

This brings us back to the beginning, to the Inuit duels. There are many contemporary examples to watch, like this one dubbed The Competition Song. They are genuinely strange to listen to, the game is played by two women facing each other closely, then one starting the beat with a strongly accented sound and the second replying with a weaker sound. Motifs are cycled, throat singing is employed as are animal yips and calls, the beat is held and sometimes increases and the players need excellent breath control to last more than a few seconds.

To bring together our themes of competitive duels, poetry/music and vocal techniques/mimicry, I wanted to touch on the art of beatboxing. This genre feels strangely fitting since it was birthed as a part of hip-hop - one of the few mainstream verbal battle formats - but has incorporated vocal techniques such as throat singing as it has matured. Contemporary beatboxing today has advanced rapidly, to the point where artists can produce multiple sound effects simultaneously whilst perfectly imitating synth and digital/analog instrumental sounds. They have also pioneered incredible feats of breath control, utilising inhalations to keep a smooth output, whilst also creating bizarre and novel sounds to include in their songs and battles. In a 2021 paper, scientists who had analysed the vocal tracts of beatboxers using MRI reported:

We found that beatboxers can create sounds that are not seen in any language. They have an acrobatic ability to put together all these different sounds …

… the beatboxer was able to generate a wide range of sound effects that do not appear in either of the languages he spoke. Instead, they appeared similar to clicks seen in African languages such as Xhosa from South Africa, Khoekhoe from Botswana, and !Xóõ from Namibia, as well as ejective consonants — bursts of air generated by closing the vocal cords — seen in Nuxálk from British Columbia, Chechen from Chechnya and Hausa from Nigeria and other countries in Africa.

-Segmentation and Classification of Beatboxing Acoustic Voice Tract Variations in MRI through Image Processing Technique (2021) A.Sinha

Researching this meandering set of topics was like discovering one series of rabbit holes after another - Norse poetry duels, Altai throat singing, modern Siberian revival bands, lost Ainu breath battles - and they all point in the same fundamental directions, to the human necessity for music, for poetry, for confrontation and co-operation. I do think there is also something important about the pastoralist world with regards to both poetry and music. I’d like to spend some more time with this idea that different ‘culture-language’ families have developed musical forms specifically to communicate with animals. I’ll leave you with this, the possible origins of the Sirens from the Odyssey…

Local names for kulning imply the alluring of animals by magic properties of sound to suggest certain behavior to the herd, avert evil trolls and predator-animals—following shamanic tradition of maiden singing. In Swedish mythology, forest spirits possessed their own cattle, and herdswomen (kulerska) learned kulning from skogsra, “sirens of the woods”. Folk beliefs attributed this power to beauty. Indeed, well-ornamented high “warbling” register of distant female voice made men and women pause their work and enjoy the sounds…

Pastoral spells in Altaic tradition constitute female prerogative, but are occasionally performed by men. The same applies to whistling signals, used across Eurasia by herdsmen to stimulate and/or safe-guard animals. Just like kulning, in pastoral societies whistling is associated with sorcery and is thoroughly regulated by taboos. Acoustically, whistling comes closest to “kula” in distance-range, loudness, and tonal quality. To command their animals, Altaic herdsmen produce whistles audible over 4–5 km, and throat-singing—3 km.

-The pastoral origin of semiotically functional tonal organization of music (2020) Nikolsky

An entire folklore or mythology of over-the-top violence developed, full of stories, legends and even place-names (“Fighting Creek”, “Gouge Eye”) to commemorate particularly notable encounters. As this folklore developed, so the combat took on a more ritualised nature, which included elaborate verbal duels – the media press conferences of the day – where combatants would take it in turns to brag of their skills. Sometimes, these boasts were powerful enough to prevent combat. Take this electrifying boast from champion gouger Mike Fink, from well over a century before Muhammed Ali made verbal blows as much a part of the modern boxer’s repertoire as physical ones.

“I’m a salt River roarer! I’m a ring tailed squealer! I’m a regular screamer from the old Massassip! Whoop! I’m the very infant that refused his milk before its eyes were open and called out for a bottle of old Rye! I love the women and I’m chockful o’ fight! I’m half wild horse and half cock-eyed alligator and the rest o’ me is crooked snags an’ red-hot snappin’ turtle… I can out-run, out-jump, out-shoot, out-brag, out-drink, an’ out-fight, rough-an’-tumble, no holts barred, any man on both sides the river from Pittsburgh to New Orleans an’ back ag’in to St Louiee. Come on, you flatters, you bargers, you milk white mechanics, an’ see how tough I am to chaw! I ain’t had a fight for two days an' I’m spilein’ for exercise. Cock-a-doodle-doo!”

Raw Egg Nationalist (Charlie Cornish-Dale) The Savage Art of Gouging https://www.raweggstack.com/p/essay-the-savage-art-of-gouging

This post sponsored by Nefarious Hexificus https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dVSjvh4vdpM