Does This Face Scare You? The Serenity Of Terror

Horror Masks: Origins of the Western Face in the calmness of the Greco-Romans

In my absence I have been working on an extended project of original research, which I am now excited to start sharing with you. Over a series of articles I aim to explain my theories about why Western masking traditions and the Western face is so different from other cultures. Using horror masks as the focus, we will explore together the metaphysics of the European face and mask, skin and pain, horror, the sublime, identity and the self - starting with Greek serenity and culminating in digital AI horror. I truly believe that this is a new contribution to the way we think about the face and the function of horror as a genre. I sincerely hope you enjoy.

Part One: The Serene Face of Terror

Some time in the late 1800’s a young woman was pulled out of the Seine at the Quai du Louvre. She was dead, maybe 16 years old, and she was flawless. The story goes that the coroner who examined her body was so moved by her beauty, so enraptured by her perfection, he fashioned a wax death mask from her face. A plaster one soon followed. These masks quickly sold out in Paris as many writers and artists rushed to hang her smooth likeness on the wall - Nabokov, Rilke, Man Ray. Camus compared her to the Mona Lisa for her subtle smile and serene expression. Louis-Ferdinand Céline sent her picture to a publisher that wanted a photograph of him. Eventually her perfect face became the model for novice painters, and the CPR doll ‘Resusci Anne’. One theory as to why her death mask appears so beautiful is that the coroner had already made a mask of his young daughter while she was alive, but she committed suicide by jumping into the Seine. To us contemporary viewers this mask seems morbid enough, but after surrealist artists dressed her in wigs, put her in bed, and made her replica skin-mask come alive by opening her eyes through photography - she crossed over into the realm of the uncanny and the horrific.

Death masks are just one example of the European fascination with preserving, and idealising the face of the dead. The Western face is the seat of identity, and to place a mask over it is to play or manipulate with that identity. To wear a calm, serene expression can turn the face itself into a mask, protecting what turmoil truly lies beneath. This article will explore this particular type of face and mask - its evolution from the archaic world to science fiction. I will make three main claims:

The Apollonian futurism of Greece invented the smooth, symmetrical human form of the modern android

The Roman development of stoic, impassive visages personified their use of terrible, dispassionate violence as a corrective response to disorder

Modern horror inherited the serene face/mask and used it in multiple registers - as a symbol of Roman-style violence against transgression (slashers), as an uncanny facial presentation (psychological horror), and ultimately as a marker of human abstraction and disappearance (sci-fi horror)

I want to flag here that the West is not the only civilisation to invent facial serenity. African equivalents like the Mblo, Dan, Punu maiden and Guro masks, the Buddhist face of enlightenment, and the Japanese Noh masks similarly emphasise symmetry, beauty and a lack of strong affect. That said, I will hopefully demonstrate through this series that horror is a uniquely Western genre, and - for reasons we will discuss in another article - Japan has been the only external culture with enough metaphysical, psychological and aesthetic resonances to the West to make a serious and long-lasting contribution to horror media.

A Brief History of Masks

We have almost no evidence of true masks for the aeons leading up to the Neolithic, most likely due to the materials degrading over time. Palaeolithic human-animal figurines, paintings and even Mesolithic antler headdresses have been identified in the archaeological record, but we have to travel to the Neolithic Near East to find any really convincing examples.

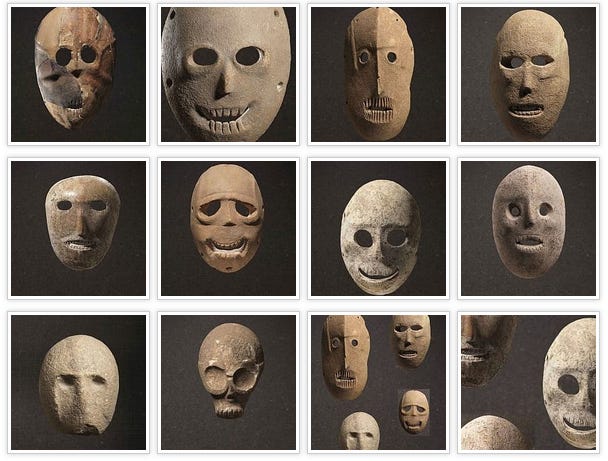

These stone masks date to around 7,000 BC, during the Pre-Pottery B phase of the Neolithic. They have been found all around the Judean Hills, in caves and parts of the desert. Their function is unknown, but the faces are strikingly eerie and modernist in appearance. Many bare their teeth, sometimes as a grimace, other times like a malevolent smile.

Since that time period, masks have become an increasingly common topic within archaeological and anthropological research. Masks for festivals, ceremonies, warfare, secret societies, theatre, religious rites, protection, amusement and burial are all well known and described in the literature.

One basic division amongst the array of masks in the image above is who the disguise was intended for? Masks do disguise the wearer, but many masks and costumes around the world are created to fool, mimic, mirror or engage with the supernatural world and its human agents (Fang Ngil masks, Japanese Oni masks, Mah Meri masks), rather than other human beings - a function known as apotropaic magic. Of course many are intended to frighten, intimidate, amuse, delight and entertain people - but we should bookmark this original function of masks, as it diminishes and almost disappears in Europe.

Suffice to say that we know little about the deep origins of masks. Carvings and depictions of human faces are rare (see the Russian Mesolithic Shigir Idol) in the deep archaeological record. Globally masks are used in all sorts of creative ways, and often the mask itself as an object possesses a form of agency, the mask is a being which can impose itself over the wearer. Examples include tutelary spirit masks amongst the Kpelle people of Liberia, Hopi dance masks which are ritually fed to appease them, and Vajrayana Buddhist Cham masks worn in Tibet.

As we will see throughout this sequential exploration of masks and faces in the Western tradition, apotropaism and mask agency become metaphysically marginal, as the face and the mask evolve within a system of thought that comes to idealise, moralise, internalise, fracture and hollow out the human self. I believe the face is central to this development, as are masks, and the tensions within this system are best explored and revealed through horror.

Greco-Roman mirrors of the divine

To save time I will simply state up front one of my given axioms - the ancient Greeks invented the idea of Nature - this doesn’t seem a hugely controversial argument and I leave it up to the reader to explore the topic if they wish. Greek naturalism was certainly influenced by Egyptian depictions of the divine, as an ideal form. Greek art revolutionised the human body by grounding its portrayal in reality, but a reality which saw the body as ultimately perfectible, with an ideal form imitating or mirroring the beauty of the divine. This made Greek civilisation (and its inheritors) a futurist culture. The Greek imagination was populated by androids and automatons such as Talos, the robotic-bronze man who guarded Crete, the story of Pygmalion & Galatea, and the creations of Hephaestus - his android golden handmaids, mechanical cauldrons and divine commission to manufacture Pandora. Greek anxieties around Pandora are the first known concerns about the unknowable behaviour of an artificial intelligence.

One face in particular though was birthed here, and has continued to be used as the symbol of progress-oriented science fiction, and that is the visage of Apollonian serene calm. This face is symmetrical, smooth, stoic, expressionless or with minimal expression, disinterested, flawless, youthful, standardised and eternal. For the remainder of this essay and beyond we will simply call this the serene face. The Greek and Roman examples we will examine are: sculptures, death masks and cavalry masks. Both of course had other mask styles, most notably the expressive theatrical types, but these will be covered another time.

Greek naturalistic sculpture is so well known there is little need for a full exposition. From the Archaic to Hellenistic period the overwhelming power of the sculptural arts to project an increasingly detached, menacing and yet utterly composed and serene face is breathtaking - in particular Kritios Boy (c. 480 BC), Polykleitos’ Doryphoros and Diadoumenos (c. 435 BC) and the Lysippus Alexander (c.330 BC). The Romans continued this tradition, with depictions of Augustus, Marcus Aurelius and Antinous, to name a few.

The Romans also enjoyed death masks (the funerary imagines). Aristocratic families kept images, replicas, busts and plaster/wax face masks of their ancestors, and it became a tradition that the living family should don these masks during a funeral to welcome the deceased. The sight of a public procession led such lifelike faces, which would have eventually distorted through fire and smoke, must have been unnerving for onlookers.

Finally the Roman cavalry masks (Nijmegen, Ribchester, Kalkriese styles) truly exemplify something approaching ‘serene horror’. The juxtaposition of violence and indifferent calm ultimately points us to the deeper logic of Roman metaphysics. If the Greeks were future-oriented, the Romans were order-oriented. For Rome, chaos was the ultimate terror, which licensed them to undertake brutal violence and inflict incredible suffering in the name of extinguishing disorder and punishing transgression. The cosmos was harmonious, and they would see it remain so.

Thus the Greek serene face signifies natural beauty, perfection and divine symmetry. The Roman serene face signifies natural hierarchy and cosmic order, emotional stoicism, legal discipline and pitiless indifference when dealing out corrective violence.

Angels and Mortals: The Renaissance to Modernity

Readers will forgive the jump to the Renaissance, but the medieval era will be covered in great detail another time. The uncovering of antiquity during the 15th and 16th centuries saw the serene face being re-imagined and redeployed across southern Europe. One way was through the choice of how to depict Biblical angels, the second was the artistic innovation of the human and the human face.

Today angels are almost always pictured as serene and calm, but this was not inevitable. In the Hebrew and Near Eastern traditions, angels are terrifying, many-eyed, disturbing beings. But in southern Europe, shaped by Greek ideals and Roman order, angels were remade into serene, symmetrical figures: they became the face of cosmic authority in the style of classical harmony. Renaissance Europe chose the calm angelic face because it suited a worldview in which order reveals the divine. As we will see, this serene, flawless face later became a template for impassive horror masks and the unreadable visors of modern science fiction.

Portraits and depictions of Christian or Classical mythology, through sculpture and painting, continued the old lineage of calm faces. Renaissance ideas of the micro and macrocosm, good and evil, also became refracted through the idea that masks were often concealing something corrupt (Carnival and Dionysian masks will be covered another time). Thus Cesare Borgia’s ‘smallpox mask’, the Morosini helmet and the serenity of the Venetian ‘larva’ mask existed alongside Michelangelo, Botticelli, the aloofness of Mannerism (Bronzino, Pontormo) and the eventual climax of Enlightenment rationality. Recovering Europe’s Greco-Roman inheritance helped keep the Apollonian face front-and-centre, emphasising classical virtues and rational control of the mind. Neoclassical portraiture repeated the Roman motif of a stoic and impassive imperial gaze, unperturbed and reflecting cosmic order.

Even as the Enlightenment gave way to the Romantics and the Gothic sublime, the wheel of progress turning towards industrialisation, revolution and war - the serene face continued to haunt Europe, channelling the archaic stillness of silent menace. Death masks and wax heads became very popular, incorporating elite and deviant alike, thanks to Marie Tussaud during the Revolutionary Terror in France. Modernist art from de Chirico’s androids to Khnopff’s hauntingly odd Symbolism repeated and expanded the face, while the mask became smoother and more abstract for Bauhaus and Triadic ballet. With modernity came psychological depth and with individuation came alienation, the impassivity came to appear uncanny and enigmatic - the metal mask of Roman order is replaced with the imposed expression of outward control. Beauty, orderliness, serenity, perfection, control, abstraction, blank, inscrutable, empty. The serene face becomes a mask, as the self goes inside, external violence replaced with internal trauma.

Sci-fi and Futurism

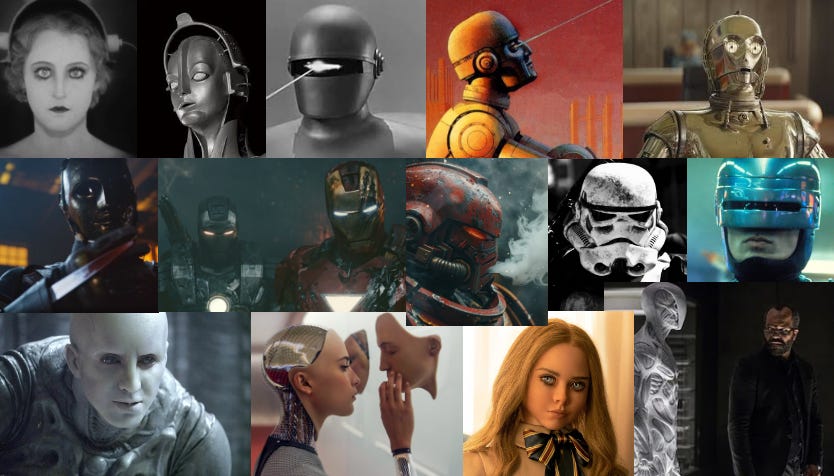

The preservation of Greek futurism through the Western imagination was obvious as soon as science fiction began creating art. In Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis, the character Maria is transformed into the Maschinenmensch - a glowering robot modelled explicitly after classical artworks. Gort, from The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), C-3PO, the androids of Asimov’s writings, Star Trek’s Data - these are smooth, serene, Apollonian figures. Symmetrical and idealised.

The Roman gift to science fiction came soon after, as impassive masks and helmets became staple features of law enforcers, punishers, avengers, soldiers, judge-like figures who dealt out death and violence without emotion. Robocop, Iron Man, the Space Marines of Warhammer 40K, Storm Troopers of Star Wars and Spartans from Halo. Their brutality is in the service of correcting transgression and maintaining order - cold blooded, emotionless and impersonal.

Although we today can look back at the Roman cavalry masks and see dread - horror as a genre is a post Enlightenment struggle between the bounded self and the eruptive numinous (more on this in another article). Therefore its only in modern cinema, gaming and art do we finally see sci-fi making use of the serene face to provoke a feeling of terror, uncanny fear and horror. Films and series like Prometheus, M3gan, Westworld and Ex Machina lean heavily on the smooth, flawless visage - draped over the technology like a mask, yet betraying none of the human affects. The serene face becomes horrifying when it no longer expresses order, but rather indifference or predation, inhuman.

Apollo Returns With Terror: Serene Horror Masks

Now we arrive at horror proper - the films, television, games and other media made from roughly the start of the 20th century, carrying the weight of the Gothic, theatre, war, modernist art, literature and photography. Masks of serenity appeared very early, the 1925 Phantom of the Opera and 1926 Faust used calm angels and the archetypal, almost Venetian, smooth mask to cover the Phantom’s disfigurement.

In the 1960 film Eyes Without A Face, Christiane is forced to wear a permanently empty and featureless expression through her mask. This visage was a landmark in cinema horror. The film intentionally looked back to antiquity for the costume, and it became hugely influential, with Mike Myer’s Halloween mask imitating her total calm - in doing so echoing the Roman warrior on horseback of millennia earlier. We all know that slasher villains appear suddenly, to punish violations of taboos and social norms, often preserving only the final virginal woman. This became such an established trope that slasher movies began to satirise it with Scream. However, few have made the connection between the masks and the actions. The classic slasher villain is impassive, silent, calm and procedural in their formulaic violence. They don’t seem to relish their work, but simply deal death. Arguably then, the calm horror mask is the Roman face returning - a disciplined, impersonal force that punishes rather than enjoys.

The serene face does not end with masks though. The angels of Constantine, Hellraiser: Judgement, the twins of The Shining, Damien from The Omen and Nina of the Black Swan also unnerve and frighten audiences with their calm, joyless faces and composed affect. Apollo has continued his reach into the 21st century, seeking beauty in perfection and dispensing cold punishment.

The serene face has become a self-contained Western visual and aesthetic grammar. It has evolved from Greek beauty and proportion to Roman indifferent punishment, through medieval and Renaissance angelic calm, youthful symmetry and scientific rationality, before turning inward onto the self and becoming abstract, blank and ultimately devoid of humanity with the arrival of the android. It turns out that horror is the perfect medium to explore this rich legacy and rivalry between the face and the mask - masks of serene correction, faces of catatonic repression, artificial beings of uncanny menace.

In the next article I will set up the counter-tradition to this southern serene - the northern numinous. In contrast to the classical emphasis on harmony, beauty, symmetry, smoothness and stoicism, the northern European imagination is about the sublime, terror before the divine. Expect shape-shifting, instability, confrontation and the grotesque.

If you enjoyed this work please consider a paid subscription or browse my books on Amazon. I always aim to write high quality articles covering the macabre and darker sides of anthropology and archaeology, as well as coverage of contemporary science topics and my own personal takes on philosophy, history and art. Your support really helps me continue this project, thank-you!

Makes me think of Mordred's mask/helmet in Excalibur.

Roman mask on the right? https://content.api.news/v3/images/bin/73af058ec2fb277038c4741273df5e75