How The West Invented Horror: Irrationality, the Uncanny and the Unstable Face

The Gothic-Romantic counter-attack, the rise of psychoanalysis and how modernity produced horror through internalisation

In my absence I have been working on an extended project of original research, which I am now excited to start sharing with you. Over a series of articles I aim to explain my theories about why Western masking traditions and the Western face is so different from other cultures. Using horror masks as the focus, we will explore together the metaphysics of the European face and mask, skin and pain, horror, the sublime, identity and the self - starting with Greek serenity and culminating in digital AI horror. I truly believe that this is a new contribution to the way we think about the face and the function of horror as a genre. I sincerely hope you enjoy.

I. Introduction: Horror as the Daughter of Rational Man

Horror emerges not from “primitive fear,” but from the cracks in Western modernity’s greatest invention: the rational, bounded, introspective individual.

Why does horror exist? Why is it a genre at all, don’t we all have a fear response?

The answer to this is not immediately obvious, and its certainly not universal. All human societies and civilisations had some kind of monsters, ancestral or animistic spirits, demons, supernatural threats, other realms and worlds — but only the West produced horror in the modern sense. Only the West developed a tradition where fear is not a simple experience to be avoided, but one to be contemplated, performed, aestheticised, and ultimately used as a mirror for the modern, psychological self.

Something unique happened in the centuries between the Enlightenment and the early twentieth century. The human being — in European thought — became a fully-fledged individual, a rational agent with a stable interior life. The Enlightenment built on its Classical-Christian inheritance, evolving the idea of a self that could be known, controlled, examined, perfected. This new, bounded person became the basic unit of modern society: the legal subject, the moral subject, the political subject and the national citizen.

Building this rational individual meant extending and developing complex philosophical ideas about how the internal self operates, how it relates to the soul (if that even existed?) and insisting on a harmonious unity. Whatever darkness lurked inside Man could be expunged in the clear light of truth and reason.

Romanticism sensed the flaws here immediately. The Gothic sensed it even earlier. These movements were the first cracks in this Enlightenment façade. They suggested that, beneath the symmetrical order of the rational self lay something older, darker, more numinous — a reservoir of instinct, violence, longing, compulsions, vices and terror. Thus the Gothic castle, the revenant, the ancestral curse, haunted portraits, vampires: all early attempts to map this interior landscape. The decisive turn came with the rise of psychoanalysis - a scientific system which insisted that the self was not one thing, but a battleground. Freud’s notion of the uncanny — the familiar made strange — was a key moment in the development of horror, a late stage of internalisation.

Horror ceased to be a theological problem or a moral allegory, and it became a psychological event: the return of what the self must exclude in order to remain ‘rational’. As the self fractures, horror breaks loose. Not an external monster, but a shadow of the rational mind. Without a cosmological framework to maintain stability, the individual cannot contain its own depths, there is no limit to this interior, an abyss. Western Man became something new - rather than taking the advice of the Greeks and becoming profound through superficiality - he turned inwards, finding both new heavens and novel hells.

II. The Enlightenment: Building the Rational Individual from the Outside In

The modern self was constructed over many brutal centuries, coming to emphasise rational introspection to build an optimistic, progress-oriented society.

Inventing the individual was a centuries long project encompassing multiple streams of thought, theological argument, dense philosophical texts and creative legal judgements. Many were ultimately rooted in European Christianity, such as Man’s inner conscience and natural law, both of which came to be derived from natural and rational principles rather than divine revelation. The concept of ‘looking inwards’ had been central to medieval monastic and scholastic introspection - St Augustine, Ockham, Aquinas - and although it had been tempered by external, earthly authority, interior examination was continued during the Renaissance by Petrarch, Pico della Mirandola and Erasmus. The Reformation electrified this tension through Luther’s insistence on the primacy of conscience:

I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe

The creative destruction of Protestant thought produced Calvin, the Anabaptists, the Swiss Brethren, the English Dissenters, the Zwickau Prophets; Batenburgers; Restorationism and countless more. Alongside this flowering of religious conscience came the Scientific Revolution, with its eventual emphasis on rational and empirical methods for revealing the truths of nature. Man’s place in a divinely ordered universe seemed assured, even as Europe slipped into the agonies of the Thirty Years War, the English Civil Wars, the French Fronde and numerous conflicts of restoration, monarchical rule and nation-building. The darker nature of Man was on full display, and the Enlightenment movement which came out the other side had to grapple with load-bearing ideas such as scepticism, freedom or liberty of thought, conscience, speech and association.

European order balanced on a knife edge of tyranny and chaos, and the individual self had to practice self-discipline, rationality and toleration to keep society from sliding one way or the other. Balance, harmony, symmetry and clarity. Portraiture from artists like Allan Ramsay and Anton Graff emphasised the southern, serene face - a calm and cerebral poise which allowed truth and virtue to shine through. Despite this veneer, the Enlightenment was always in a state of flux and conflict, both within its ‘Republic of letters’ and from its external critics. By the 1770’s the individual self may have acquired great legal, economic, social and religious liberties, constituted on rational, scientific progress - but it was about to undergo its first major trial.

III. Romanticism and the Gothic: The Counterattack

he smites an uncouth animation out of the rocks which he has torn from, among the moss of the moorland, and heaves into the darkened air of the pile of iron buttress and rugged wall, instinct with a work of an imagination as wild and wayward as the northern sea; creations of ungain1y shape and rigid limb, but full of wolfish life; fierce as the winds that beat, and changeful as the clouds that shade them

-The Stones of Venice (Vol II), 1853, John Ruskin

In 1756 the Anglo-Irish politician Edmund Burke had laid out a crucial argument, one which would move the emotional response of simple fear from primitive to contemplative. Burke was the first thinker to split the concepts of beauty and sublime, that sublime was a feeling of awe, wonder and fear before something much greater than oneself. Being trapped on a boat during a storm produced terror beholding the raw power of nature. Seeing a painting of such a storm invoked this feeling, at a distance, causing a paradoxical delight and even pleasure in the viewer. Art could use the triad of terror through obscurity to give pleasure through the sublime.

The British Gothic responded to the Enlightenment in a typically English way - by using older, ruined or abandoned architecture as a metaphor for the haunted and repressed psyche. Castles, half-overgrown monasteries, windswept moors become stages for barely glimpsed monsters and ghosts which ultimately illuminated the interior world of the mind. Walpole’s medievalism, the fusion of Milton’s defiant Satan with a transgressive supernatural villain and early bourgeois anxieties about industrialisation - this witch’s brew produced an enduring aesthetic movement in love with twilight, gloom, forbidden desire, dangerous eros, beauty and terror, the troubled inheritance and hubristic tragedy. German and French equivalent literary genres existed (Schauerroman, roman noir), dealing far more with visceral horror and moral corruption, but it was the British Gothic which pushed psychological depth to its height in the late 18th century.

Romanticism was the wider oceanic swell in which the Gothic surfed, an upsurge of momentous feeling which has never culturally receded. Turning away from calm rationality, the Romantics looked simultaneously backwards and forwards, to nature, primitivism and medieval enchantment, and to revolution, experimental art and expanding empathy towards animals and the disenfranchised. The German Sturm und Drang, The Sorrows of Young Werther, Chatterton’s suicide, the French Revolution, the primacy of individual subjectivity and even emotional turmoil and crisis - Romanticism created the West’s love affair with the tormented genius, the rebel and the tension between duty and passion. The Sublime was to be found in the overwhelming power of mountains, oceans, caves and landscapes, but also in the mysterious and thrilling terror of summoning ghosts, of nightmares, apparitions, visions, sleepwalking, altered consciousness and madness. Terror was not just for moonlit nights, but also experienced in the obscurity of the human mind and the deeper subterranean forces which threatened to seep out and swallow men whole.

IV. Psychoanalysis: The Internalisation of Chaos

“Bow or not? Call back or not? Recognize him or not?” our hero wondered in indescribable anguish, “or pretend that I am not myself, but somebody else strikingly like me, and look as though nothing were the matter.”

-The Double, Dostoevsky

Knowingly or not, the writers of Gothic fiction had begun exploring an idea which would become central to the lives of Europeans even today - the return of the repressed. That Man had an inner life was not new, the ancients knew that, but Romanticism had opened the door to a new kind of subjectivity. Kant suggested the mind containable unknowable regions beneath rational cognition, Schelling and Fichte pushed into them - the dark unconscious strata of the self. Carl Carus explicitly named it, Fechner studied it. The German Romantics sketched out doubling, repression, dream-life and the uncanny through Herder, Goethe and Hoffman. In France, Maine de Biran, Ribot, Charcot and Janet laid the clinical and psychological foundations for dissociation, trauma and instinctive or automatic behaviours. Darwin, Spencer, Edward Tylor, James Frazer, Jakob Bachofen and Max Muller expanded the depth of human time and breadth of human culture, opening up vistas of development and branching within consciousness itself. By the time Nietzsche, Breuer and finally Sigmund Freud came to name and systematise the disturbing layers of Man’s inner world, European thought had spent over a century building the foundational architecture of the modern mind.

Freud famously explained ‘the uncanny’, or Das Unheimliche, in his 1919 essay - describing this ‘unhomely’ feeling as the return of the repressed. The familiar becomes unfamiliar, alien and dreadful. Long buried childhood fears suddenly snap into view through the symbol of a doll, a frozen face or the sensation of repetition. I’ve dreamt of this moment before. The uncanny has lost much of its precise meaning today, and is best known for the endlessly discussed uncanny valley effect. For Freud and the early psychoanalysts the uncanny, along with the structure of the mind, the unconscious, defence mechanisms, slips in speech or behaviour and psychosexual development, constituted a specific phenomenon. Presenting the uncanny through fiction is difficult, and Freud was clear that while fiction gives an author more license to develop uncanny moments, there is a distinction between the uncanny in reality and in literature/film.

Psychoanalysis is a fundamental pivot point in the development of the Western horror genre, and thus, under the surface, also of Western metaphysics concerning the self, identity, the face and the other. External terror in the form of monsters and demons became thoroughly internalised, not just as guilt or shame, but as the blueprint of the Western psyche. Almost all horrors have, since Freud and modernity, been taken into the mind - doubles, doppelgangers, the omnipotent child, the devouring mother, the gaze of the other, bodily fragmentation and alienation, our body as foreign or containing a contaminant, possession, the death drive, forbidden knowledge, repression, the uncanny, breach of taboo, the power of naming, castration/blinding/cannibalism/phallic anxiety, dissociation, hysteria and many, many more. Horror is now an internal genre, and any horror media which does not utilise this psychological angle feels simple, quaint and almost primitive.

V. Modernity and the Uncanny: When the Self Itself Becomes Unstable

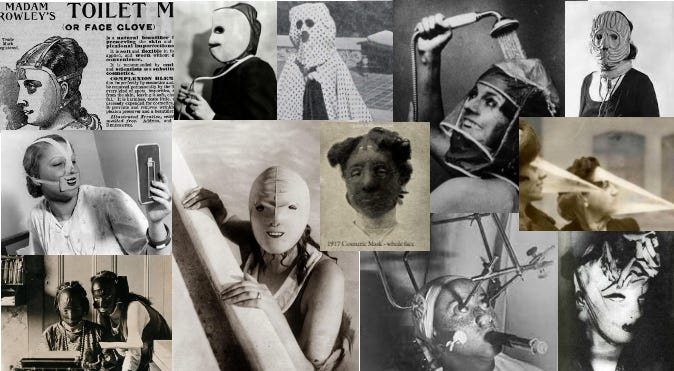

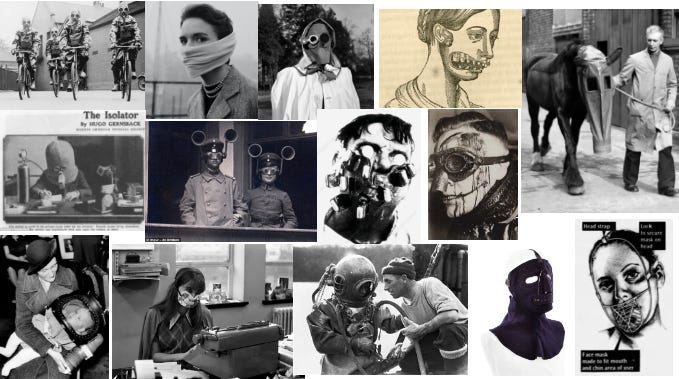

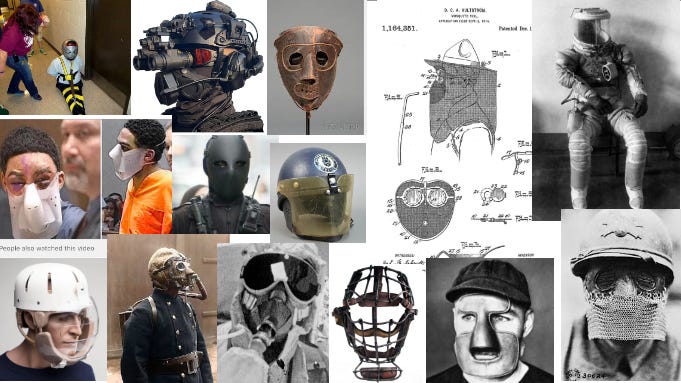

Psychoanalysis was not alone in birthing the modern self. Industrialisation, secularisation, middle-class urban culture, mass democracy, the world wars and bureaucratisation all played their part. Selfhood and identity became vastly more internal and self-reflective, whilst the physical body underwent multiple rounds of discipline, correction, control and legibility. Everything from the criminal face to childhood education was put under the microscope of scientists and innovators, producing mini-factory floors in every setting. The face as a whole was ever more reproducible and visible, yet disembodied, through photography, cinema, advertising and art. The Industrial Revolution demanded new faces, new skins - welding masks, goggles, respirators, diving suits and eventually fully operational gas masks (see my bonus piece on gas masks for more details)

We can list out how the face changed as modernity began and picked up pace:

Death masks, realistic wax statues/busts, mass produced dolls, mannequins

Victorian fireplace masks, fans, mourning veils, death and spirit photography

A continuous stream of beauty treatments, masks, visors and facial apparatus, including phototherapy, compression and jawline masks

Development of the cinema face - silent film, technicolor, prosthetics,

Military helmets, gas masks, splatter masks, aviation/flame/cold weather masks, sniper/anti-shard/ballistic masks

Diving, mining, smoke, welding, mountaineering, radiation, UV masks and respirators

Post-WW1 surgical prosthetics, tin-masks, medical masks/visors, lead-glass eyewear, anaesthesia masks, post-war flu masks

Sporting helmets and masks in hockey, baseball, motorcycling, skiing

Shift from traditional blackface guising/mumming to Halloween monster and franchise costumes

Policing helmets, balaclavas and riot facial protection, anti-spit/bite masks, restraint hoods, prison and psychiatric anti-self harm headgear

In the traditional visual arts, the face undergoes a radical transformation. In stark contrast to the Pre-Raephelites, Neo-Classicism or French Realism, modernist art begins to destabilise the face, seeing it not as an eternal vessel of identity - but as a vector for internal incoherence. The Impressionists dissolve it into atmosphere, a fleeting configuration of light; while the Symbolists turn the face into a psychic screen - masklike, withdrawn, eroticised, empty. Post-Impressionism fractures the face: Cezanne abstracts it with planes, van Gogh charges it with emotional violence, Gauguin mythologises it into primitive archetypes. By the turn of the 20th century the face is deliberately smashed. Picasso, Braque and the Cubists finally destroy Renaissance-derived perspective and the face is flattened and broken into a collage, an assemblage. Futurism takes the face and tries to smear it across time, identity split by velocity and speed. German Expressionism (Kirchner, Nolde, Heckel) distorts the face into intentional masks of rage, grief, anxiety, derangement and madness. Weimar artists like Dix and Grosz use the face to convey social unravelling, through war injuries, make-up, hyper-realistic and unpleasant visages. Surrealism uses the smoothed out, rubbery, mask-like concept of the face and facial skin to melt, distort, mutate and collapse identity into dream-like anarchy. Max Ernst even hybridises the face into an ‘animal-becoming’ collage. In a climax of ‘northern-grotesque’ angst, Francis Bacon completely shreds any metaphysical unity left in the human face - creating howling vortices of flesh, metal, wounds, trauma.

New media like photography and cinema heralded radical new ways to display and manipulate the face. People and their emotional states were abstracted away from a living breathing being, but simultaneously we had never before had such an intimate affair with the face, which could be captured in exquisite detail and frozen in time. Photography could reveal a serious but loving family portrait, a momento mori serene face of a dead child, uninhibited and unstaged erotica, extra heads as a baby moved back and forth during exposure, ghostly apparitions of ancestors and spirits, the almost comically-creepy hooded ‘hidden mother’ clutching children in her lap. Georges Méliès combined this technology with movement and demonstrated how the face and body could be fully malleable to any desire, with clones of himself singing, throwing his own head around, faces merging with objects (go watch his 1902 short, A Trip to the Moon). Cinema required stage-like exaggerated facial features, chiaroscuro make-up, mask-like emotional performance - until the technology improved enough to fill the entire screen with faces. Luminous fields of emotivity could be generated by filmmakers, such as German Expressionist horror; Soviet political montage; Surrealist violation - then Hollywood’s Apollonian mask of beauty, all engineering parasocial feeling within the viewer, whilst the embodied person behind the face retreated. Facial detachment, facially uncanny, visually immediate but insincere. The face could no longer be trusted as a genuine portrayal of the other.

The Tale of the Mannequin and the Ventriloquist Dummy

Freud explored the uncanny through Hoffman’s tale of the Sandman, focusing on the automaton’s uncannily lifelike qualities. Two examples of similar humanoid constructions can also be compared to show how the ‘southern serene’ and ‘northern grotesque’ came together during modernity’s turn into the interior. Mannequin dummies have their origin in Renaissance art technology, drawing on an idealised human form, smooth, symmetrical and proportionate. Mannequins found multiple later uses in Europe for dressmaking, medical anatomy, art and eventually storefront advertising. Their calm, still, objective and smooth form is in direct contrast to ventriloquist dummies or puppets. Although ventriloquism as an art form is culturally widespread and makes use of animals, masks, hands, cloths and other people - European ventriloquism matched well with the Germanic-style puppet. Their jerky movements, unnatural faces, gaping mouths and often mocking, sardonic voices perfectly exemplify the ‘northern grotesque’ lineage. Where the mannequin was compliant, pure and represented order, the ventriloquist dummy was intrusive, chaotic - an eruption of the performer’s id into riotous misrule. The mannequin obeyed, the dummy was restrained.

Little wonder then that their uncanniness produced horror and desire in viewers and owners. Psychoanalytical and early psychological work identified agalmatophilia and automatonophobia, pygmalionism, pediophobia and many other odd fears and attractions towards these human-like objects. Sexual attraction, overwhelming terror, uncanny emotions provoking childish regression, anxieties and desires of being turned into a puppet or a doll, of being made out of wood, of feeling empty and faceless. Modern horror and science fiction is simply impossible without this internalisation of feeling towards androids, dolls, puppets and robots.

VI. Conclusion — Horror Exists Because the Western Self Cannot Contain Itself

Put simply, the West invented horror because the West underwent a singularly unique transformation, a total revolution in human life, which involved discovering or creating previously unknown psychological depths. Horror is the shadow of this transition, that which can never be sublimated or neatly categorised. Horror wears the skin of former fears, but exists in the mind - monsters become metaphors, haunted houses the sites of unresolved traumas, possession is madness, childhood toys return as uncanny phobias, demonic temptations reinterpreted as repressed desires. Modernity changed us, and it changed our faces - which were peeled from embodied men and women, and fractured, distorted, rearranged, engineered, sculpted through photography, cinema, advertising, art and war. Faces floated on screens, tugging emotions from audiences, who in the outside world covered themselves in ever-advancing layers of second-skins, visors, helmets, goggles, masks, prosthetics and make-up. The face was no stable no more, split apart by the forces of Freud, trench warfare, industrial advance, visual technology and painters. Precarious, shattered, smoothed, abstract, doubled, desired, feared.

Now that we have this framework in place, we can begin to dig deeper into the Western metaphysics of the face through topics like smiling, possession, the skin, pain, eroticism and a contrasting piece with Japanese horror. Next time we’ll explore the skin (through horror) as the true metaphysical boundary of the individual - removing it, adding it, changing it, growing it…

If you enjoyed this work please consider a paid subscription or browse my books on Amazon. I always aim to write high quality articles covering the macabre and darker sides of anthropology and archaeology, as well as coverage of contemporary science topics and my own personal takes on philosophy, history and art. Your support really helps me continue this project, thank-you!

Very enjoyable read! You have one little slip when you wrote “The Sorrows of Young Goethe” when you certainly mean “Young Werther”

Great piece.