Skin: Two Millennia Of Surface Horror.

A unified theory of flaying, naturalism, prosthetics, shapeshifting, skin-magic, sainthood, face-lifts and deepfakes

In my absence I have been working on an extended project of original research, which I am now excited to start sharing with you. Over a series of articles I aim to explain my theories about why Western masking traditions and the Western face is so different from other cultures. Using horror masks as the focus, we will explore together the metaphysics of the European face and mask, skin and pain, horror, the sublime, identity and the self - starting with Greek serenity and culminating in digital AI horror. I truly believe that this is a new contribution to the way we think about the face and the function of horror as a genre. I sincerely hope you enjoy.

Skin is the Real Mask?

Over several articles now, we’ve been able to sketch out a rough theory of how masks, the face and identity, horror and the self have functioned in Europe in different times and places. In brief:

Greco-Roman (southern serene) - calm, Apollonian, idealised, smooth. Divine terror and masking controlled through public and group-based ceremonies, festivals

Northern-Germanic (northern numinous) - eruption, chaotic, grotesque. Divine terror and masking expressed through confrontation, intrusion, liminality and external threat

Modern horror emerges as a response to the breakdown of Enlightenment individual rationality in the face of modernity, systematised and internalised through psychoanalysis. Both southern and northern faces/modes integrated.

With this basic scaffolding in place we can deepen our analysis, and begin to fill in the blanks, starting with two linked articles - this piece on skin and identity, and the second on smiling, possession and sincerity.

So what’s my claim? Skin is the most intimate mask of Western civilisation. Where other cultures might animate their masks with spirits, the West has always insisted that identity lies beneath the surface, in the flesh, nerves, psyche. It seems absolutely true to me that the Western mask is completely inert, and the real, true site of possession, horror, or transformation is the skin itself. Skin is the container, the surface wrapping or even ‘envelope’ which both presents and encloses personhood. Skin is the mask of the deeper self, and when removed, modified or damaged instinctively leads to ambiguity about that self. Before the horror mask came the dread of skin, the body’s mask. A space for horror arrives whenever the skin can no longer guarantee stability, identity, or integrity, as we shall see.

Greco-Roman Naturalism, Skin as Divine Surface

The Western metaphysics of skin begins in classical naturalism. To the Greek mind, surfaces were everything. As we’ve already seen in earlier articles, Greek idealisation of the human form created artistic/religious representations as well as real physical bodies, which aligned with their vision of divinity. Theologian Thorleif Boman wrote, “Greeks, who find beauty in the plastic”, summarising the Greek tension beneath the visible and invisible - mysteries which should not be explored.

The Greeks knew and felt the terrors and horrors of existence; in order to live at all, they had to place in front of these things the resplendent, dream-born figures of the Olympians.

Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy

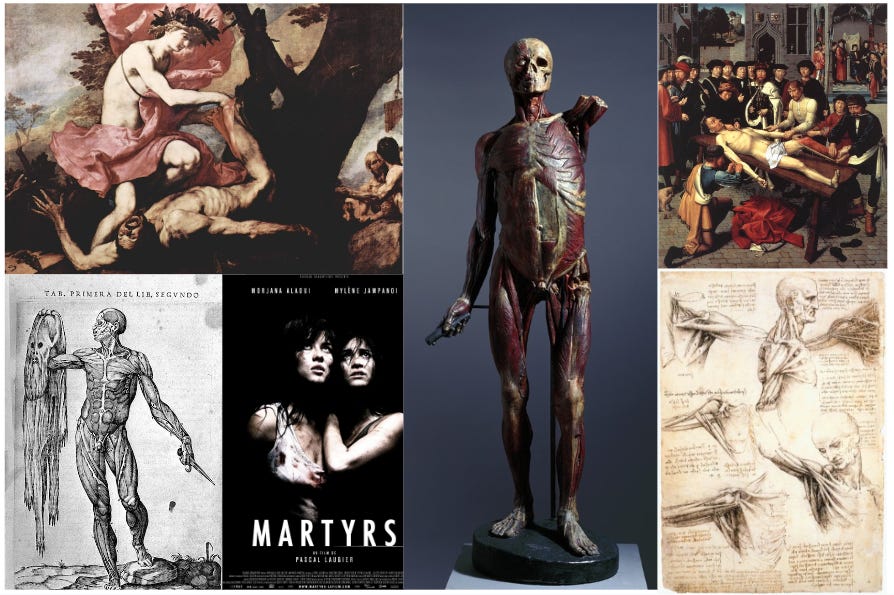

Surfaces were an expression of divinity, and the Greek mind managed the struggle between mind-body, sea-land, god-human, us-them - by conjuring fictional idealisations, allowing them to go above and below the surface just enough. Greek proto-horror (we could say the aestheticisation of terror) revolved around violating this surface. Medusa petrified her victims, rendering their perfect exterior frozen for all eternity; Marsyas attempted to challenge the divine harmony, and was flayed alive by Apollo for his hubris; Dionysian sparagmos, the tearing apart of a human body, an inversion of sculptural bodily integrity; leaving corpses for the animals to eat, or desecrating a corpse as Achilles did Hector - forms of the Greek disgust at the stigma, marking and puncturing the skin. All these horrors indicate Greco anxiety at surfaces and skins being opened, the inside spilling out, the body failing at its boundaries.

Of course, the Greeks did wear masks: theatrical, communal, ecstatic. But these were not like masks elsewhere, which in themselves added something to the skin, in an animistic or religious sense. Masks were not alive. To don a mask during public festivals or witnessing a blind, bleeding mask on the stage, was not to invite the divine in through the mask. Skin ultimately remained the divine surface.

After Greece, Rome: Roman attitudes to skin evolved from idealisation into an extreme naturalism, or verism. Harmonious form was recognised, but Roman skin was turned towards the outward, legible record of citizenship. The body’s surface was politicised, and depictions of virtuous citizens proudly displayed scars, wrinkles, age, lopsided features and every marker of gravitas. Conversely, this surface record could be unmade through violation. Damnatio ad bestias, crucifixion, scourging. Enemy leaders were mutilated not for spectacle alone, but to erase their public identity.

A citizen whose skin was torn apart by beasts lost not only life but civic personhood. They were denied burial, memory, and the continuity of their name. Their face could never be recreated in wax and paraded with their ancestors, the imagines maiorum, since the face needed to be intact and politically acceptable.

One of their civilisation’s most profound fears is found in this intersection of flesh, citizenship, and public visibility: to be flayed, exposed, or defaced is to be erased from the civic and familial world.

Enemies paraded in chains are displayed as bodies whose skin will soon be violated, their future dismemberment implied by the ritual. Triumph and execution share this same metaphysical grammar, since the skin is where order can be affirmed or removed. The skin is not a spiritual veil but a social contract, a surface where identity becomes politically visible. When that surface is violated, Rome experiences the dreadful void of political dissolution. A civic body torn up as much as the human one. Rome, as ever, is the bridge between Greek corporeal metaphysics and the later Christian concern with sins, flesh, wounds and miraculous skin. The takeaway here is that the Western skin tradition starts with Greek idealisation, and then Roman politicisation. But what happened in the European north?

Northern and Medieval Skin Traditions | Skin as Moral Boundary

Christian Europe drew on multiple sources of meaning for skin, beginning with the Roman inheritance of public identity. Although not strictly Republican citizenship, medieval law codes nevertheless insisted on the skin acting as a legal document due to its obvious irreversibility: Early Germanic law was largely (not exclusively) compensatory rather than punitive, injuries were assessed, priced, and resolved through payment (weregild) instead of mutilation. As Roman models of governance spread northward, punishment increasingly targeted the body itself, with branding, disfigurement, and amputation turning the skin into a surface on which authority could be written.

Medieval Christianity also inherited a complicated mixture of attitudes towards the skin. In the logic of Judaism, to be ‘marked’ on the skin could be both good (circumcision, protection e.g Ezekiel) and bad (Leviticus). Early Christianity similarly emphasised this dualism - the mark of the beast, Christ’s wounds, saintly mutilations. The Church reviled tattoos as marks of paganism and criminality, although the Eastern Church and Christians living under Islamic rule came to re-invent them, viewing crosses on the wrist or marks of St Michael as protective. Crusaders and pilgrims picked up this attitude, and presented their absolute proof of the journey through scarification and Coptic/Armenian tattoos.

What this all has in common is the shift from a political body to the skin as a moralised boundary - a veil over the fallen flesh, sinful body and immortal, idealised soul. God’s grace could be shown through the preservation of the saintly body, which never degraded, or his displeasure extended via leprosy and plague. Punishments written onto the skin such as mutilation, beating and amputation are designed to reflect both the legal and moral/theological crime - the earthly and heavenly. The use of fire to execute becomes institutionalised after the Orléans heresy of 1022, and canonical concepts of purgatorium between 1150-1250 containing ‘purging fire’ emphasise the punishing aspect of flames on the skin. Fire neither mimicked the holy shedding of blood, nor the cruel visceral martyrdoms of the saints, but destroyed the skin completely and purged the veil of sin.

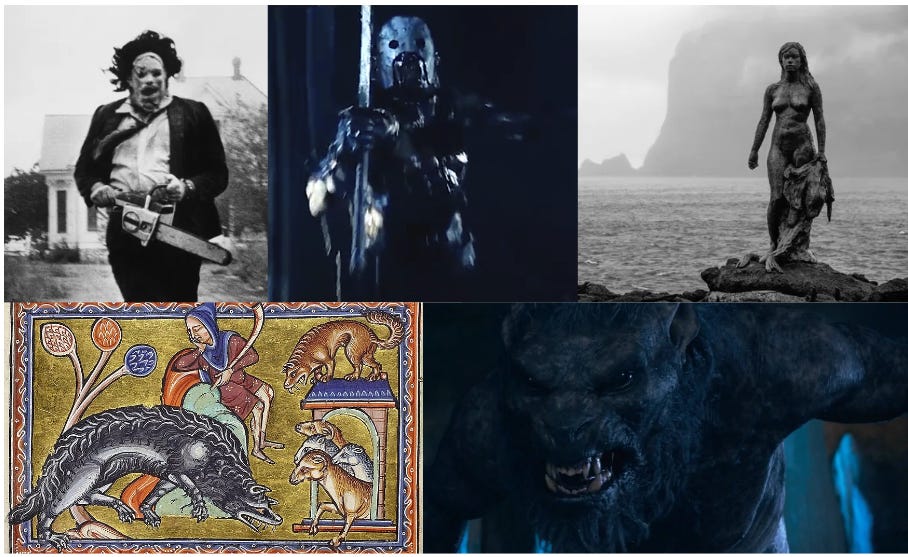

Meanwhile in northern Europe, older traditions of the skin as a membrane which could erupt were still active and preserved. As described inYnglinga Saga and Haraldskvæði, warriors enter a state of berserksgangr (‘bear-shirt’ or ‘bare-shirt), the skin metaphorically altered with swelling, heat, morphing and invulnerability. Identity erupts through the body, rather than expressed symbolically or legally. Change breaks through the skin, and the skin can cause change, an object in its own right. Werewolves demonstrated a similar belief - Marie de France’s Bisclavret, the Irish Ossory werewolves - here the skin is a removable and transformable boundary, and to change skin is to change the underlying moral and social being. At the Celtic fringes, Selkie seal-skin folklore (Orkney, Shetland, Faroes) also insists that the skin can be stolen, leading to identities being change and trapped. Returning the skin can restore the being, thus skin is an ontological property, beyond a container, boundary or surface appearance. Skin is animate, or has agency in some sense.

These two visions of the skin between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance again highlight the north-south polarity we’ve discussed, with change and harmony, legalism and chaos being front and centre. Where they meet during the process of Christianisation results in the skin being a site of intense moralisation.

Renaissance and the Enlightenment: Open it up and see what’s inside.

While the cult dedicated to St Bartholomew, patron saint of tanners and bookbinders, may have began during the medieval period - it was not until the Renaissance that the lurid fascination with his martyrdom truly took off. The poor man had been flayed alive. Medieval skin was theologically rich of course, but the Renaissance celebrated what was to become a fundamentally Western orientation to the world - what is underneath the skin, what is inside? Flaying as a form of punishment has always been exceptionally rare and likely a poorly managed spectacle (leaving aside the Assyrians, who cared little for the soul or moralisation of the skin, and simply flayed, then nailed up skins as a demonstration of imperial power, skin’s owner’s personal identities are irrelevant). Despite this, the unease and horror of being flayed alive plays on the human mind, and has produced some immense artworks, reflecting this crawling terror of being intentionally separated from our skin. The artwork of flaying is not a story for here, but suffice to say the Renaissance was able to depict it more graphic detail due to the new appreciation of perspective, the body and its skin.

Thus from the 15th century onwards, skin becomes a threshold to be opened, studied and perfected. Proto-science emerges through early anatomical theatres, where the skin is removed and the deeper layers of body revealed before an audience. Renaissance alchemy and magic located cosmic influences within the skin. Skin could be used for its metaphysical properties, as well as read as a surface betraying inner truth. Vesalius peeled back the surface to reveal a body composed of structures, fibres, and tensions. The opened corpse was arranged, posed, and displayed as evidence. At the same time thinkers such as Marsilio Ficino and Paracelsus continued to treat the skin as a porous membrane through which astral and elemental forces acted. Disease, temperament, and fate were still imagined as entering and exiting at the surface. Marks on the body: scars, growths, anomalous nipples, were read as signs of invisible influence. The skin remained legible, but it was no longer metaphysically sacred.

Medieval punishment was often less, shall we say, anatomically inventive than this early modern successor? High medieval justice usually relied on fines, exile, outlawing, hanging or simple beheading- all methods intended to remove the offender rather than systematically work on the body. Its only in the early modern period, especially from the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, that routine punishments and torture become technical, prolonged and surface-focused: the rack, the strappado, breaking on the wheel, judicial burning, boiling and carefully staged executions designed to extract confession, deterrence and brutal spectacle. As states centralised and legal authority hardened, violence shifted from retribution to methodical inscription upon the body. Torture and execution became instruments for producing truth and obedience by acting directly on the skin.

The Enlightenment inherits this vulnerable, exposed body and attempts to stabilise it through systematisation. By the late 17th century, figures such as William Harvey, Herman Boerhaave, and Albrecht von Haller reframed the human organism as a regulated interior, governed by circulation, nerves and laws. The skin became a boundary condition, a surface separating a private, rational interior from a world to be measured and controlled. Medical classification accelerated, insisting that pathology appears on the skin, while causation retreats ever-inward. The emerging sciences of mind and body depend on this partition, e.g. John Locke’s conception of the self as interior consciousness presupposes a sealed surface that contains it.Yet this rationalisation did not resolve the unease. Once the skin is defined as a barrier, its failure becomes a primary source of anxiety. The Enlightenment feared leakage rather than possession: eruptions, rashes, sores and lesions become visible signs that the internal system was breaking down.

It seems that at certain periods the dichotomous feelings towards the skin can be greatly intensified. According to Barbara Maria Stafford, the Enlightenment was one such period. The remarkable chapter entitled ‘Marking’ in her book Body Criticism outlines in detail the fascinated disgust with the pathological skin which reigned in Europe from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. The ‘aesthetic of immaculateness’ of the eighteenth century, with the smooth, white complexions of its ladies, the dazzling white lines of its neo-classical sculpture and architecture and the sumptuously bland sheen of its portraits and landscapes, was, she argues, a panicky and unstable response to the nauseating phantasmagoria of rotting, eruptive and squamous skins that constituted the actual bodyscape in the eighteenth century

-The Book of Skin (2004) Steven Connor

By the eighteenth century, the skin had become a site of surveillance and intervention - to be observed, classified, and treated, but never fully secured. Terror no longer arrived from beyond the body. It emerged at the surface, where the fragile boundary between interior order and exterior force begins to give way.

Modernity. The Skin as Material, Project and Regime

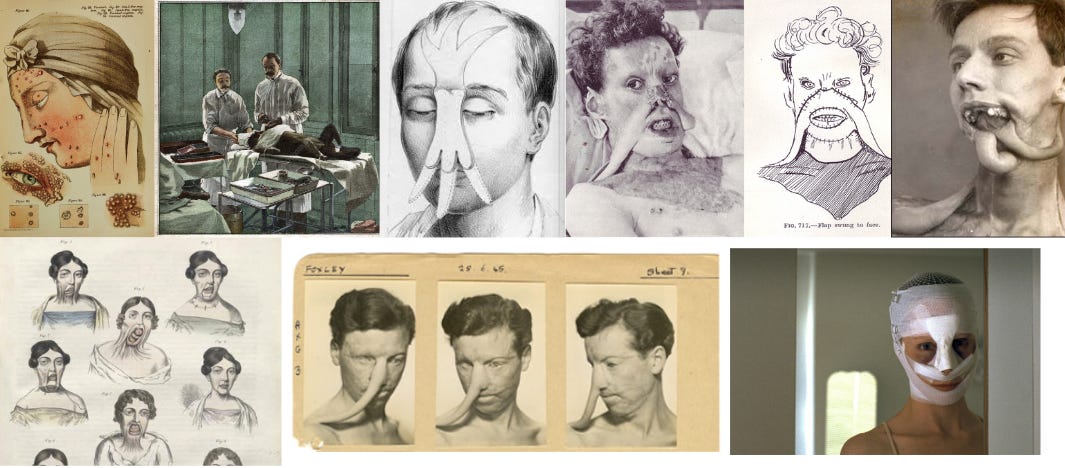

From the late nineteenth century onward, the skin ceases to be merely injured or violated and becomes something that can be systematically worked. Advances in surgery and experimental medicine transform the body’s surface into a manipulable substrate. Skin grafting techniques develop rapidly after the 1870s, driven by industrial accidents and colonial medicine, and reach its grim maturity during the First World War. Surgeons such as Hippolyte Morestin in France and Harold Gillies in Britain pioneer flap surgery, pedicled grafts, and facial reconstruction for soldiers whose faces had been torn apart by shrapnel. These procedures reconceptualise skin as modular and transferable. Early transplantation experiments push even further, testing xenografts using animal tissue and skin, and later organ transplantation. These destabilise the boundary between bodies altogether. The surface of the human becomes provisional and capable of replacement, supplementation, substitution. Identity could no longer reside securely in the skin and had to be reconstructed, sometimes literally stitched together from borrowed matter.

Alongside this surgical manipulation emerges the modern discipline of skin maintenance. Practices that were once associated with trades such as butchers, tanners and leatherworkers are gradually displaced by hygienic, medical, and cosmetic frameworks. By the early twentieth century, dermatology separates itself from general surgery and pathology, while commercial cosmetics industries expand rapidly in Europe and the United States. Skin care became a daily obligation rather than an occasional intervention. You must wash, exfoliate, moisturise, protect, tan. The surface of the body subjected to continuous regulation. One’s skin must be actively produced and vigilantly preserved to maintain health. Smoothness, youth, and uniform tone become newly moralised ideals, presented to the world evidence of one’s discipline, vitality, and self-control.

This regime intensified throughout the twentieth century. Chemical peels, early hormonal treatments, ultraviolet tanning lamps, collagen injections and later synthetic fillers promise to correct, preserve, and optimise the surface. Masks and creams, which were once ritual or theatrical are now routine technologies of concealment and repair. The language of care slides seamlessly into the language of control, and to neglect your skin is to fail oneself. Injury and pathology are equally reframed through maintenance: scars softened, burns disguised, pigmentation corrected. The body’s surface becomes a site of constant anxiety, monitored for signs of decline or disorder.

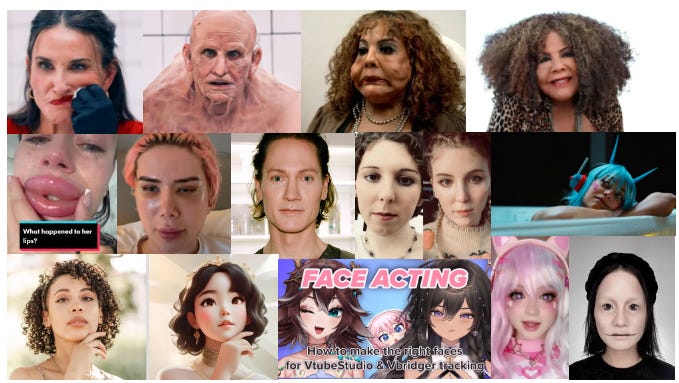

Beneath the seductive promise of this care routine is a fairly anti-human logic: the skin is no longer a metaphysical boundary that guarantees identity, but is rather a mutable interface to be managed. Modern horror emerges with the recognition that the self has been reduced to a surface under permanent maintenance, endlessly repairable, endlessly correctable, and never complete: see the 2024 satirical body horror The Substance pushing this concept to absurd heights, comfortably viewed alongside TikTok clips of grotesque filler and injection mistakes. To be comfortable in one’s own skin can feel like a social rarity in the contemporary world when new bodily dsymorphias keep being discovered, and transgender medical care promises the Promethean dream of completely rearranging the skin to match the interior identity. As Judith Halberstam argued in her 1995 work, Skin Shows: Gothic Horror and the Technology of Monsters, older Gothic ideas of monstrosity fall away under modernity’s ability to swap, alter and change the body and skin. What is immutable becomes more problematic.

Modern Horror: Case Studies

Having covered the trajectory of the Western interest in skin, boundaries and selfhood, we can now look at what horror reveals to us through stories and images. As previously argued, the horror genre exists because modernity created a new psychological depth and mental structure which results in dread, fear, terror, phobias, the logic of the uncanny - each person contains a permanent tension between their conscious and unconscious selves. Since skin is the ultimate boundary of these selves, it becomes a ripe arena for projections and artistic visions where the self and identity come under extreme threat.

The French psychoanalyst Didier Anzieu argues, in his 1985 book The Skin Ego, that Western subjectivity is built through the psychological interdependence of real tactile skin and the mental ‘skin ego’ wrapping or envelope, which contains the stable self. We still say that someone is ‘thin-skinned’ or needs to develop a ‘thicker skin’ to describe their internal resilience and ability to keep from being psychically wounded. Patients who have lost their physical skin to third-degree burns often present as regressive infants, the sensation of totalising pain de-centering consciousness, making a coherent ‘I’ impossible. Using this lens of the skin-ego, we can see how the different Western models of the skin-as-boundary have been explored in cinema, through four films.

In The Silence of the Lambs (1991), the skin ego is framed as a problem of containment and identity transfer, given life through two figures who embody opposite solutions. Buffalo Bill’s fantasy of literally “wearing” another’s skin is an attempt to manufacture an envelope that he cannot generate psychically. This could be seen as Renaissance-coded in its literalism, the skin treated as a detachable garment, and yet the fantasy is modern in its surgical logic: the body is really just a material to be cut, shaped, and assembled into a new surface. The skin’s temporary wearer should rub the lotion on the skin, in preparation for its new host. Arguably though the film’s true structure comes from the later Enlightenment, with its investigative gaze, classificatory apparatus, clinical spaces, a procedural language that assumes the human is an object of study. Clarice Starling moves through these spaces and institutions which try to read human surfaces, looking for truth. Dr Lecter himself sits serenely behind glass like an idealised, perfected envelope. He is the opposite of Bill, he presents a sealed interior on almost public display, a Roman-style civic, stoic face transposed into modern transparency. The horror is not that something ‘possesses’ the self (a medieval fear), but that the barrier fails or must be replaced, a very modern anxiety of leakage and intrusion. If Anzieu says the self is held together by an envelope, then Silence of the Lambs explores what happens when that envelope is unlivable and the subject seeks a substitute in the flesh.

If Silence is an Enlightenment/modern procedural film about surface as identity, then The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) can be seen as a medieval-northern nightmare of pre-symbolic life, where the psychic skin envelope never properly forms. Leatherface is not a stable villain, but rather a being who requires external skins simply to function. Each flayed mask is a crude prosthesis for an absent psychic boundary, haphazardly wrapped around his head to show the barest semblance of a face to the world. I interpret this as the northern dynamic at its most extreme: eruption without containment, the berserker logic of pure affect breaking through the surface, but stripped of all heroic mythos and reduced to sheer panic. The family home is an upside-down ‘anti-household’, a grotesque parody of the hearth. Where the medieval oven is a site of domestic order and sacramental warmth, this horrific interior is a slaughterhouse, a tragic inversion of nourishment. The meals are humiliation, the kinship is animalistic noise. Leatherface attempts, or is pushed to take up the role of the absent symbolic feminine, as ‘cook’ and ‘carer’, but utterly fails to cohere this identity within his skin. The resulting violence is not stylised like a Greek tragedy or Roman spectacle, it is a process, abattoir-like, almost industrial. Bodies are treated as hides, the human reduced to the animal surface worked by tools and hooks. The film has cultural staying-power because it depicts a world before the civic and theological systems that once stabilised skin with meaning. Like a state of nature in the outer dark (rural Americana), there is no Roman personhood to violate, no medieval soul to damn, no Renaissance curiosity to even dignify the bloody exposure - only the fact of skin as a base material, and the terror of a self that cannot be held together.

Goodnight Mommy (2014) flips this previous structure entirely. In this Austrian horror film the skin ego envelope exists, but the moment of terror comes when recognisability collapses. The mother’s post-surgical face, all bandaged, altered and temporarily suspended between two forms, this becomes an embodiment of the modern condition: repair but without reassurance, reconstruction but without psychic continuity. Arguably this is modernity’s surgical regime crossing over into metaphysics. The unfortunate children experience the maternal face surface not as a comforting haven but as an uncanny facade: the skin appears technically ‘correct’ yet fails to display the affective signature which once made it trustworthy. The horror is not northern eruption but verification, not unlike a fairy changeling, except here the facial skin has a double problem - the outer layer of bandages, the inner layer of raw wounded dermis - which is hiding the real mother? The children’s eventual cruelty functions like an obscene Enlightenment experiment: pain as epistemology, torture as proof of interiority. Their question is utterly primitive, “does this skin still contain my mother?” The maternal body once guaranteed protection as an enveloping presence, but in the film the envelope has become unreliable. In Roman terms, the face is the seat of recognisable personhood. For the boys, her personhood is thrown into doubt by this repaired surface. The film’s dreadful chill arises from the premise that identity can be medically preserved yet psychically lost, that the skin can survive as an interface while the self, for the child, no longer ‘arrives’ through it. We moderns cannot even cling to the succour of fairies stealing and replacing people, for now the skin-interior-self layers are all medically and psychologically legible, reproducible, divisible, fungible.

Finally, Martyrs (2008) is possibly the most extreme articulation of my proposed Western skin logic, because it makes skin/envelope-destruction purposeful. Where Greek sparagmos tore the body apart in Dionysian frenzy, Martyrs replaces this ecstasy with a precise method, a kind of modern administrative violence that turns suffering into procedure. In one sense the core concept of the film is pure Renaissance in its detached fascination with what lies beneath the skin, yet it also echoes or summons up a medieval-like theology of pain, with visions of purgation and ultimate sanctification through visceral bodily process. However, I think the film’s real symbolic engine is completely modern. The disciplined enclosure, institutional rhythm, the reduction of the subject to a pure surface that can be acted upon repeatedly until symbolisation fails. What happens to the terrified victims is a systematic dismantling of their skin ego, through blows, confinement, deprivation, humiliation - each one eroding the envelope that allows a person to still remain a person during adversity. The cult’s aim in the film is a total metaphysical hollowing, to produce a consciousness beyond the boundary of the skin, a self emptied of selfhood. A person still alive without their skin is not truly a person - they are a mythical creature of total agony and de-centred consciousness, what Ovid described as “one vast wound”. Martyrs goes beyond ‘body horror’ as the mere mutation of the human body, and creates a symbolic horror-process for achieving human vacancy. When the container is peeled away, how can the interior still hold?

Taken together, these films show how Western horror cycles through its own history of the surface. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can be interpreted as the northern abyss, a skin without symbol, an envelope never formed. The Silence of the Lambs is an Enlightenment/modern surgical imaginary, the skin as an identity-project, with substitution, theft, and control. Goodnight Mommy is a modern reconstruction which turned metaphysical, the skin preserved as an interface but recognisability collapses. Finally Martyrs is a fusion of medieval pain-theology with modern technique, envelope destruction as truth, hollowing out as transcendence. Across all four films, the older European motifs still remain metaphysically important, such as the classical faith in the surface and the northern fear of eruption, the medieval moral reading of flesh, the Renaissance appetite for exposure, the Enlightenment obsession with classification and interiority, modernity’s surgical remaking of the human. Modern horror is not just a neutral medium though, it gladly recombines these themes, whilst showing us that the direction of travel is consistent. From skin as the guarantor of personhood, towards skin as a detachable layer, and in the contemporary media landscape of AI faces and synthetic media - a new implication is on the horizon: if skin can be generated without a body, and the face can circulate without a self, then the West’s oldest boundary becomes a perfectly stable surface which contains nothing.

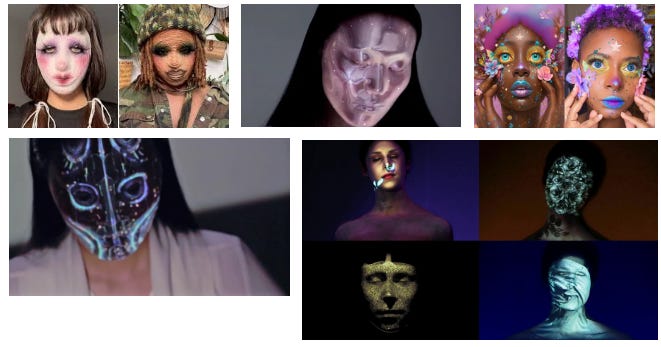

Post-script: Digital Horror and the End/Triumph of Skin

Contemporary horror media is increasingly converging on a point where the skin and interior will finally separate. In digital culture, the surface can no longer cover, protect, or really reveals anything beneath it. Instead it functions autonomously. Filters, avatars, manipulated faces and generative skins all present a body without any flesh and a face without any visible biography. Horror will migrate accordingly. The terror will no longer be that the skin can be torn, flayed, or invaded, but it will remain intact while nothing exists behind it. This is what I call the logic of hollowing: the surface perfected to the point of emptiness.

Digital horror repeatedly stages this condition. In games such as SOMA (2015), identity persists as a skin-like interface, with voice, memory, facial continuity, all the while consciousness itself is endlessly copied and abandoned. The body is no longer visually violated, it is irrelevant. Similarly, The Mandela Catalogue and other analog/digital hybrids fixate on faces that appear to be human but fail to contain a person, with eyes that look correctly but do not gaze back, smiles that persist without real affect, surfaces that can simulate expression but really signal vacancy. In Black Mirror episodes such as Be Right Back and White Christmas, synthetic bodies and faces reproduce intimacy without interiority, generating horror through perfect continuity, absent self-presence. Analog skin eventually lies, betrays and fails, digital skin is immortal.

This marks a decisive break from classical body horror. In films like The Fly, Videodrome, or Martyrs, the horror depends on rupture. The skin splits, mutates, peels, or collapses under pressure. Identity is threatened because the envelope fails. Pain, transformation, and invasion still assume that something inside is being exposed or destroyed. Even the most extreme corporeal horror retains this metaphysics of depth, that beneath the skin there is a self or soul to lose. Body horror is only terrifying because the interior really is vulnerable.

Digital horror will reverse this logic, precisely because there is no depth to violate. Nothing needs to break. The face persists, smooth and functional, and interiority evaporates away. I posit this is why contemporary horror is moving, and will move, to a focus on glitches rather than wounds, uncanny stillness rather than gore, faces that linger just that little bit too long. Gone are the gorno fears and pleadings against bodily death or physical mutilation, future-oriented horror is encountering a surface that no longer corresponds to any kind of real underlying selfhood. Earlier horror explored what happens when the skin fails, digital horror presents what happens when the skin surface itself is near-divine.

With this in mind, I argue that nascent digital horror is not a new genre but one possible expression of a long Western trajectory. Greek serenity idealised the surface and the Romans politicised it, the northern imagination feared its rupture and medieval Christianity moralised it, the Renaissance opened the skin and the Enlightenment sealed an interior within it, finally modernity learned to cut, graft, and maintain it. Now the skin has been emancipated from the body entirely. It can be generated, inhabited, exchanged, and circulated without clear origin. This piece therefore ends where Western metaphysics seems to be headed: towards a face that does not bleed, does not decay, does not open - and does not contain anyone or anything. Skin, once the ultimate mask and vessel of the self, has become a perfectly stable interface over nothing, nothing at all.

If you enjoyed this work please consider a paid subscription or browse my books on Amazon. I always aim to write high quality articles covering the macabre and darker sides of anthropology and archaeology, as well as coverage of contemporary science topics and my own personal takes on philosophy, history and art. Your support really helps me continue this project, thank-you!

"Aaaaah a cute anime girl talking to me through the computer I'm going insaaaane!!"

BTW if you have access to X, last Halloween I participated in a space where I recited a few local werewolf stories from the 18-19th century, in a few of them the source of the curse was a wolf skin that the person was forced to wear by the devil and could be physically destroyed to free them https://x.com/Ancient_Daze/status/1983654998363054542

The argument linking Buffalo Bill's literalism to Renaissance skin-thinking is really sharp. There's somethign almost tragicomic about the way modernity gives us surgical tools to "fix" boundaries we can no longer psychically hold together. I watched Silence again last year and what stayed with me wasn't the procedural investigation but that basement waiting room scene, the way the film lingers on the victim behind glass, skin still intact but already treated as raw material. Its Enlightenment surface-reading meets assembly-line horror. The skin-ego concept cuts through alot of vague body horror discourse too, explains why some films land viscerally while others just gross us out without real dread.