The Prehistoric Fortresses of Eurasia

Agricultural forts in the West, forager forts in the East

Common wisdom would assert that organised warfare and all its trappings belong to a social age far beyond the hunter-gatherer band or nomadic tribe. Architecture, pottery, metallurgy and social stratification mentally map onto agriculturalists at the very least. Marxist and post-Marxist theories about economics, production and surpluses still dictate to researchers and observers alike that simple foragers cannot move up the technology tree without abandoning hunting and taking up some form of settled, permanent farming. It keeps coming as a shock then, that hunter-gatherers did indeed build grand and monumental architecture, and that they devised ways to keep others out.

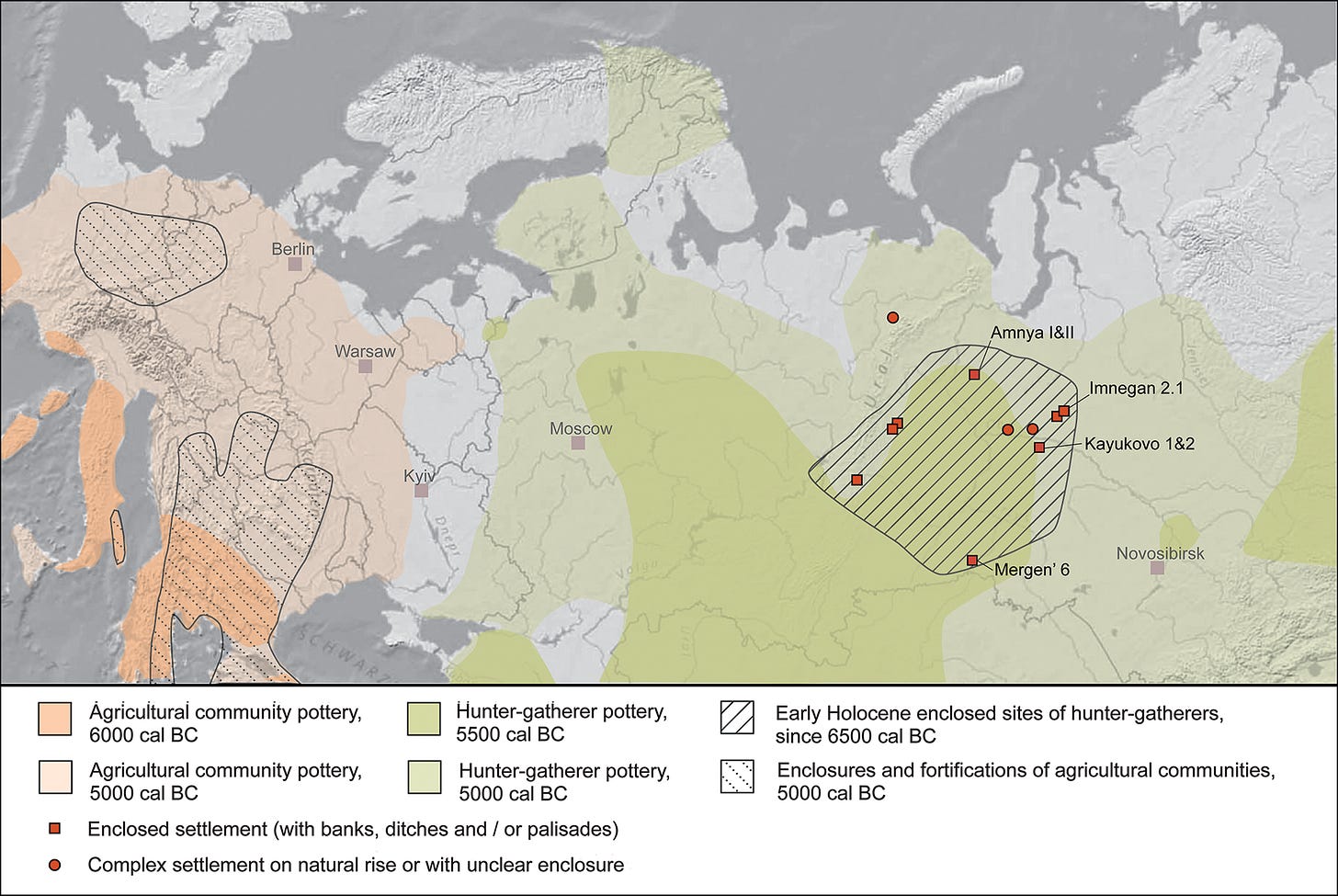

A paper published in Antiquity last December was another one of those shocks. It details recent excavations at a western Siberian site called Amnya, radiocarbon dating a fortified hunter-gatherer settlement to 6,500 BC - the oldest in the world so far. The authors lament in the introduction how little attention the subject of defensive warfare has garnered within European academia. American scholars working on Native American archaeology know all too well about coastal fortresses and personal armour, as do their Russian counterparts, who have documented similar examples across the taiga. Meanwhile European academics still cling to ideas about peaceful foragers and farmers, even while the DNA and skeletal remains say otherwise.

So let us be bold, and look at the evidence we have: a western Eurasia of agricultural fortresses, and an eastern Eurasia of forager fortresses.

The West: LBK warfare

For those younger researchers coming up through the ranks of today’s institutions, the past does indeed look like a foreign country. If they were to sit down and read through the literature of the European Neolithic from the past 30 years, the picture they would come away with is one of peaceful agricultural villages, where collective monument building and earthworks happened in an egalitarian fashion to strengthen collective bonds, or something of the like. War was always a secondary or tertiary interpretation.

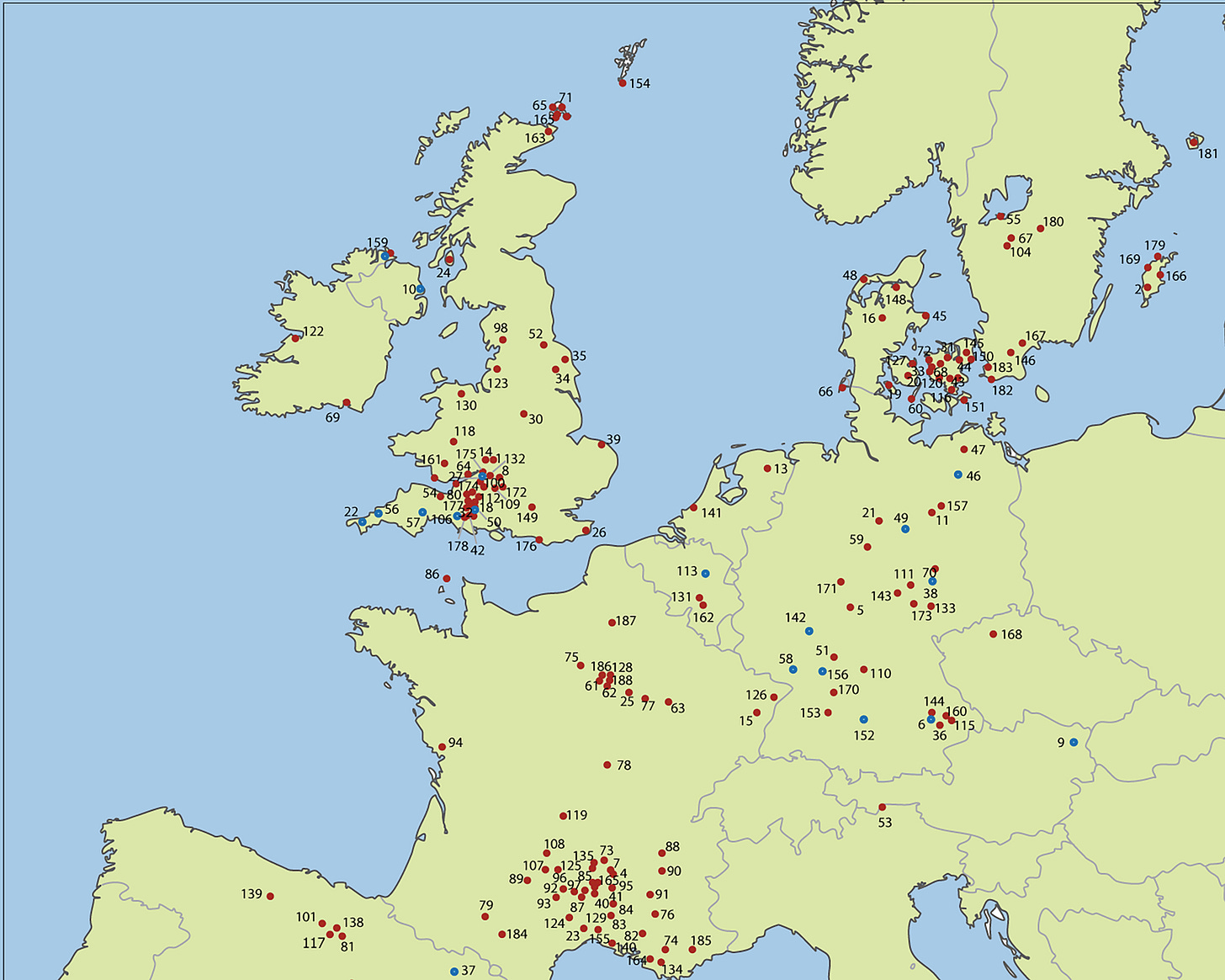

The picture today couldn’t look more different - in place of this idyllic image we have a regular stream of publications concerned with how unusually violent the European Neolithic was, even by prehistoric standards. Not only do we have extremely high levels of traumatic and lethal injuries on identified skeletons (10% of all individuals by some counts), but we also have an ever growing list of ‘massacre’ sites, where large numbers of people were brutally killed and dumped in mass graves: Herxheim, Talheim, Asparn/Schletz, San Juan ante Portam Latinam, Schöneck-Kilianstädten, Halberstadt and so on. We shall briefly look at some examples to get a clearer idea of what this Neolithic ‘way of war’ meant in practice.

Focusing on the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture - the civilisation of early farmers which swept from the Balkans to the English Channel - dating to roughly 5,500 - 4,500 BC. Towards the end of the LBK we see a tremendous amount of inter-group violence, including massacres of whole settlements. Some examples include Talheim, Asparn/Schletz and Schöneck-Kilianstädten. Talheim is now the most infamous of the group, being the earliest found (1983), where at least 34 people were thrown into a pit. Most showed traumatic skull and other bone injuries, and those that did not were presumably killed violently but exhibited only soft tissue injuries. Schöneck-Kilianstädten was similar, with 26 people identified. Asparn/Schletz was slightly different, a site where at least 67 people were killed and then dumped into the trenches surrounding a settlement site. Many showed signs of carnivore damage, indicating that the bodies were left exposed for some time, before being hastily disposed of in a pre-existing feature. All three of these sites revealed that blunt force trauma to the back of the head was a common killing blow, although at Schöneck the victims appeared to have had their legs broken prior to be killed. All ages and sexes are represented in these graves, including children. A well noted feature of the sites is the absence of 9-16 year olds, and especially teenage and young women. It seems very likely that they were taken away rather than killed.

One further LBK site of note - Halberstadt. Unlike the other graves, this mass burial tells a very different story.